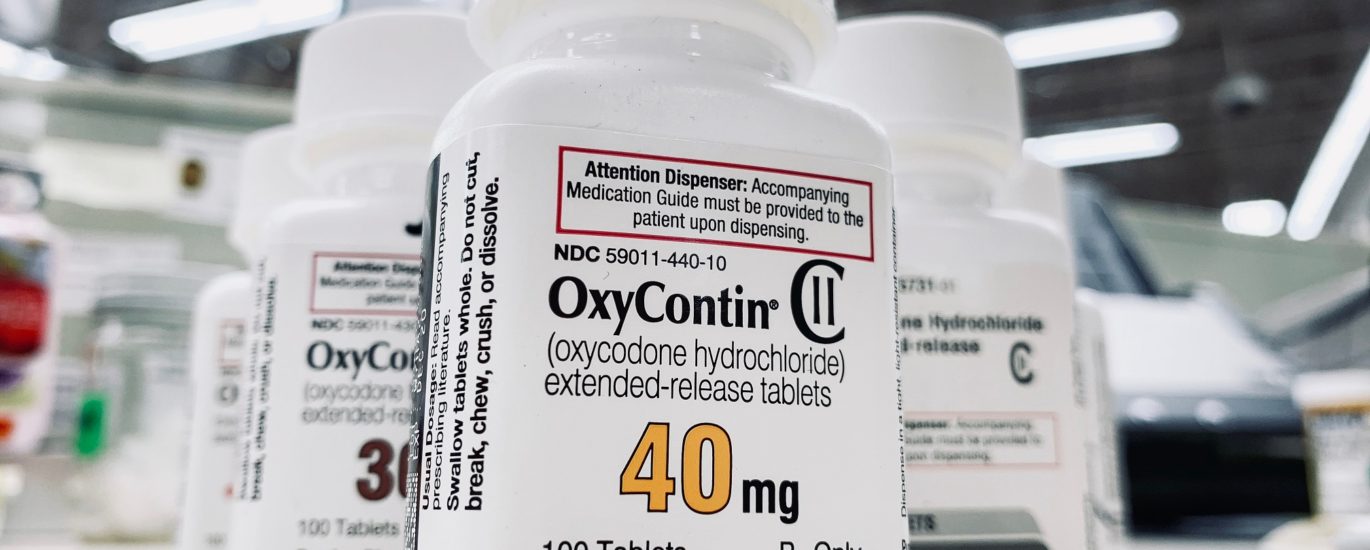

Deaths due to drug overdoses is like recounting the esoteric exploits of the Grim Reaper, and then some. Meier, a journalist by trade, writes that in 2016, 64,000 Americans died from drug overdoses. By 2021, the annual death toll attributable to drug overdoses in the USA was over 100,000, a disconcerting surge of 56 percent in five years. Many of these deaths have been correctly attributed to a class of drugs called the opioids which circulate as prescription painkillers or illegal drugs. They are compounds derived from the opium poppy plant, or alternatively synthesized in a lab. Opioids are narcotics and narcotics are nervous system depressants, meaning they reduce stimulation and arousal. Brain activity decreases upon ingestion, and an epiphenomenon of that is slowed respiration. Too high a dose and one may cease breathing. Opioids include the illegal drug heroin, and other prescription analgesics like morphine (MS Contin), hydromorphone (Exalgo, Dilaudid), oxycodone (OxyContin), and hydrocodone (Vicodin) used to relieve moderate to severe pain.

The body count has continued to climb in the last decade, thanks to the third wave of the opioid epidemic in which the synthetic opioid fentanyl has been a key player. According to Meier, the opioid crisis began with OxyContin, the “wonder drug” which started circulating in the mid-1990s. “Oxy,” as it was frequently alluded to, is comprised of pure oxycodone–advantageous over other drugs in the same class because of its longer half-life. It is tightly regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) who placed it into the Schedule II narcotic category, together with other drugs that are potent and addictive painkillers like hydromorphone, fentanyl, and morphine. Despite these prescient measures seeking to circumvent illegitimate usage, OxyContin was not immune from recreational use by drug addicts who found a way to circumvent the tablet’s time-release mechanism. First, they would lubricate the pill in their mouths and regurgitate it. Then the pill was wrapped into a creased dollar note and crushed orally, releasing the white powder onto a flat surface of choice. It was subsequently snorted. OxyContin was an arbiter of the instant high, able to propel somebody into the warm embrace of euphoria. Intravenous drug users could inject it like they did heroin. “Oxy” was available in the guise of a 10mg, 20mg, 40mg, 80mg, and 160mg tablet. Its street value was considerable, selling at $1 per milligram–hence an 160mg “OxyCoffin” as it was morbidly called by some of its staunchest detractors, would sell for $160.

Affluent civilians could sustain a habit without having to suffer the throes of financial burden but for the more impecunious it proved detrimental, digging much deeper into their pockets than they would have liked and placing considerable strain on other psychosocial domains of functioning. The inadvertent consequence was a burgeoning of disquieting systemic issues–preponderance of shoplifting and robberies, and increasing levels of disorder within provincial communities. At the absolute zenith of the opioid epidemic many chemists were held at gunpoint as armed abusers rustled frantically through pharmacy shelves scouring for “Oxys.” Bodies filled morgues as addict after addict overdosed on the narcotic. Moreover, opportunism was rife among many medical doctors who ran “pill mills” for the extrinsic rewards they offered and attracted drug addicts as pollen attracts bees. Not equipped with the essential resources and egregiously understaffed, well-meaning law enforcement officers, government officials, and health care professionals found themselves swimming in the deep, murky waters of an evolving health crisis instigated at the behest of a single albeit formidable corporation.

The scandalous antagonist of the evolving opioid crisis narrative, was in fact, the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. Owned by the Sackler family, there is a body of solid evidence demonstrating that Purdue and its executives were cognizant of the drug’s addiction potential as far back as 1998. They knew about the street abuse of both OxyContin and its predecessor MS Contin, the latter coveted on the black market because of its high concentration of morphine sulfate. In Pain Killer (2023) Meier shines a spotlight upon a study performed by researchers from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, and published in the reputable and esteemed Canadian Medical Association Journal in 1998 (1). An inadvertent byproduct of interviewing drug users and dealers in the streets of a squalid and impecunious Vancouver district was to stumble upon the grim reality that morphine was being extracted from MS Contin tablets mechanically and then injected intravenously. A cogent way around the time-releasing mechanism had been found; the outer coating would be peeled off and then the pill was pulverized to extract the morphine. The street name for a 15mg MS Contin pill was “green peeler” while the more potent 30mg version was a “purple peeler.”

Purdue Pharma also knew of the black-market potential internally, through their own drug representatives whose memo transcriptions sometimes included ways in which the tablets were being crushed to achieve an instantaneous euphoric “high.” All this cumulative data represented a salient conflict of interest for Purdue Pharma, a position antithetical to their claims about the safety of controlled-release oxycodone as well as its allegedly lower risk for misuse and addiction than heroin and morphine. When the then medical director of Purdue Pharma, Dr. Paul Goldenheim, testified under oath before a Senate panel he specified, quite matter-of-factly, that reports of illegitimate OxyContin use were unprecedented and hitherto unknown to the company. In his statement, he stipulated that in the seventeen years that MS Contin had been circulating in the market there was never any suspicion of abuse. In the aftermath, some hard facts came to light contradicting and falsifying his assertion, and casting a thick layer of doubt around the Purdue executives’ ethical sensibilities.

Understanding factors which might pose an impediment to OxyContin’s prospective sales reach, the company deliberately misrepresented data to propitiate suspicion among medical doctors about its addiction potential and concealed it from drug regulators like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the DEA. What ensued, of course, was a very aggressive and unrelenting marketing campaign at their behest that hoodwinked medical doctors into zealous overprescription, partly through financial incentives and partly through the erroneous branding of the narcotic as “safe” with potency and efficacy at extirpating pain. A determined band of activists and sales representatives made sure the erroneous word about OxyContin was spread far and wide.

The narrative climax is a bittersweet charade because Purdue Pharma’s three top executives, the men who orchestrated an impassioned marketing campaign in an attempt to flagrantly shove this opioid down the throat of every chronic pain patient in the country when they were aware of its addiction potential, did not suffer a punishment befitting the severity of the crime; they didn’t get years in prison, as the innumerable families of patients who suffered OxyContin overdoses and the <300,000 overdose victims themselves would have wished, but hours of community service. It was as if the good fairy Merry Weather had spontaneously appeared in their defense to soften a damning curse of criminal felony uttered beforehand by Maleficent and transmute it into a lesser misdemeanor charge of “misbranding.” If truth be told, it is a reflection of a gargantuan flaw in capitalism, a system of governance that allows for a few affluent and self-serving puppeteers to horde millions, often at the expense of the naïve bourgeoise, a bevy of puppets who either end up incapacitated or dead as a consequence of the violent string-pulling. This is just one of many elephants in the room beseeching attention.

Before matriculating at the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology [Sofia University] for graduate school studies in clinical psychology, I worked for Drug Safety Services (DSS) based in the precinct of Collingwood in Melbourne, Australia. At that time DSS was a Lilliputian arm of North Yarra Community Health Center. DSS was something of a one stop shop for individuals addicted to drugs. Operating from this space was a syringe service program equipped with all the usual paraphernalia (i.e., butterflies, gauge needles, alcohol swabs) for safe injecting, as well as specialized medical and allied health services and liaison/referral services for this demographic. In the span of my ten years of employment there (2003-2013) I was privy to a dismal conglomeration of overdose deaths from heroin and a family of prescription opioids that included oxycodone and hydromorphone. Philosophies of harm reduction seek to mitigate the physical and psychological burdens of opioid addiction, but if truth be told their modus operandi–chiefly dishing out prescriptions of methadone maintenance treatment–involves substituting one addictive opioid for one voluminously safer and unlikely to result in a tragic overdose; the proverbial lesser of two evils. The patient’s idiosyncratic circumstances dictated the prescription type. Sometimes the doctor prescribed methadone, sometimes buprenorphine, and sometimes suboxone.

Methadone is a long-acting full opioid agonist. Chemically, buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist and its psychotropic affects (i.e., euphoria) are attenuated in comparison to those elicited by methadone. Later, suboxone–an amalgamation of buprenorphine and naloxone, an opioid antagonist able to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose– joined the armamentarium of heroin mimics in the street fight against addiction and overdose (2). Unfortunately, the greater corpus of patients treated with medically prescribed opioids found themselves helplessness enmeshed in a debilitating and insidious cycle of withdrawal and relapse punctuated by only sporadic periods of abstinence and mental clarity. Are these government-funded drug management programs successful? A very valid question, right? That all depends on the criteria used to operationalize success. If the key and only criterion is preventing a prospective overdose, then the answer might be a cautionary “yes.” If we shift the benchmark to vocational rehabilitation, enhanced quality of life, and societal flourishing, the answer may be a resounding “no.” Success is arbitrary.

As a rule of thumb opioids carry copious risks, some of which include psychological dependency, lethargy and somnolence, increased falls in the elderly, reduced sexual drive, and sensitization to pain (3). There is a physiological acclimatization to opioid levels in the bloodstream (called physical dependence), with the user needing cumulatively higher doses to combat the development of tolerance. Protracted absence of the substance triggers the excruciating process of withdrawal, an ordeal involving flu-like symptoms like muscle aches, sweating, abdominal cramping, nausea, and vomiting. Some of the same risks exist with other sedatives like barbiturates and benzodiazepines.

Empirical research is trending towards alternative pharmacological and adjunct nonpharmacological treatments because pain patients treated under the auspices of these modalities recover faster and with fewer complications (4). In the contemporary world of craniofacial pain management, bland tension-type headaches are treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or paracetamol. The treatment for migraine headache– the eighth most common health condition in the context of disability-affected life years–is bereft of opioids, too. Prophylactic medications to decrease frequency and intensity of migraine attacks consist of an antihypertensive beta-blocker (propranolol), an antiepileptic (sodium valproate), or a calcium channel blocker (verapamil), and abortive treatments for grappling with an acute attack would be something like an analgesic [diclofenac potassium, ketorolac], ergotamine, or a triptan (5). The overwhelming medical consensus about opioids is that they should only be prescribed to patients under extenuating circumstances. For instance, they are often prescribed to migraine patients presenting to the ED with refractory status migranosis, however conventional wisdom decrees they should be eschewed due to poor efficacy, risk of rebound headache, and prolonged possible medication overuse. Medical doctors will underscore the notion that they are a suboptimal treatment option.

Barry Meier’s Pain Killer underscores one study by a pain specialist named a Dr. Jane Ballantyne, the head of the pain management department at the coveted Massachusetts General in Boston, which deserves explicit mention. This study plots an inverse correlation between chronic opioid use and improved functional outcomes (i.e., decreased levels of pain and enhanced physical function) in chronic pain patients, and attributes it to acquired tolerance for the drug (6). In her discussion she alludes to the phenomenon of building tolerance which can only be offset by increasing dose. The latter is a precarious stalemate and therapeutically ineffective. In fact, the accumulating empirical evidence strongly favors nonpharmacological treatment strategies because they are comparatively inexpensive and superior in the context of longer-term functional outcomes. Meier reports that a group of Denmark researchers discovered pain patients on nonpharmacological treatment regimens recovered four times faster than pain patients on opioids.

In much the same vein an evidence-based review article published in the Journal of Headache and Pain stipulated that behavioral management options, including psychological interventions like relaxation training, CBT, and biofeedback, are highly effective as adjunctive to pharmacotherapy or stand-alone treatments for headaches in children and adolescents with the additional advantage that they are cost-effective and void of dangerous side effects (7). Moreover, a recent expert review of neurotherapeutics serving as an update on behavioral treatments for migraine corroborated the very same thing for adults: relaxation training, biofeedback, and CBT were found to be as effective in prophylaxis of migraine headaches as the orthodox pharmacotherapies (8). Enhanced effects were observed with multimodal treatment. This might seem counterintuitive for those ardently invested in the biomedical model, but a cumulative body of robust research in pain management continues to converge on the contention that chronic use of opioids increases disability affected life years.

In the final analysis, reasons for nuclear explosions of drug use that evolve into epidemics of unruly proportions might be clearer and more palpable than we think. The issue has been complexified and become gratuitously convoluted because humans are creatures that meander along paths of least resistance, and when it comes to preservation of homeostasis and salubrious balance afforded by the societal illusion of a “magic pill,” an alkahest, the panacea… a pill able to trap pain and suffering back into Pandora’s Box and keep the ailment at bay, it is seductive and bewitching, and worthy of our undivided attention and loyalty. Once the dust settles though, the collective human shadow becomes visible. Isn’t it easier to ingest a pill and have the pain instantaneously evaporate from conscious awareness than go to psychotherapy on a weekly basis? Isn’t it easier to swallow and forget than to courageously attempt to recondition the autonomic nervous system in a way that emancipates oneself of swimming in the churning sea of their own vivid imagination, shackled to their disturbing memories and anticipation of future suffering? As hard as it is to fathom, as counterintuitive as it seems, one can still thrive and flourish without being completely pain free; one can still feel pain–minute or overwhelming, burning or stabbing, momentary or protracted–without having to suffer like a martyr or become disabled and crippled. Pain is a symptom, not a cause.

If Pain Killer has something to teach us, it is that our time of self-discovery, of relearning, and of reconditioning has arrived.

References

- Meier B. Pain killer: an empire of deceit and the origin of America’s opioid epidemic. New York, NY: Random House; 2023.

- Bell J, Strang J. Medication Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 1;87(1):82-88. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.020. Epub 2019 Jul 2. PMID: 31420089.

- Pergolizzi JV Jr, Raffa RB, Rosenblatt MH. Opioid withdrawal symptoms, a consequence of chronic opioid use and opioid use disorder: Current understanding and approaches to management. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020 Oct;45(5):892-903. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13114. Epub 2020 Jan 27. PMID: 31986228.

- Meier B. Pain killer: an empire of deceit and the origin of America’s opioid epidemic. New York, NY: Random House; 2023.

- Berkowitz AL. Clinical neurology and neuroanatomy: a localization-based approach. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2017. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1984§ionid=147770408

- Meier B. Pain killer: an empire of deceit and the origin of America’s opioid epidemic. New York, NY: Random House; 2023.

- Faedda N, Cerutti R, Verdecchia P, Migliorini D, Arruda M, Guidetti V. Behavioral management of headache in children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2016 Dec;17(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0671-4. Epub 2016 Sep 5. PMID: 27596923; PMCID: PMC5011470.

- Kropp P, Meyer B, Meyer W, Dresler T. An update on behavioral treatments in migraine – current knowledge and future options. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017 Nov;17(11):1059-1068. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1377611. Epub 2017 Sep 19. PMID: 28877611.