An

anomalous experience can be defined as a subjective, idiosyncratic, and/or

uncommon experience that is incongruent and/or deviates from the

sociocultural-mediated understanding of consensus reality accepted as veridical,

normative, and empirically valid by the collective prerogative. This definition

is consistent with the definition given by Cardena, Lynn, and Krippner (2000)

who describe it as “an uncommon experience or one that… is believed to deviate

from ordinary experience or from the usually accepted explanation of reality”

(p. 4). Moreover the word “anomalous” implies an experience with phenomenal

content that stands out because it is not “homolous” (Warwick & Waldram,

2010).

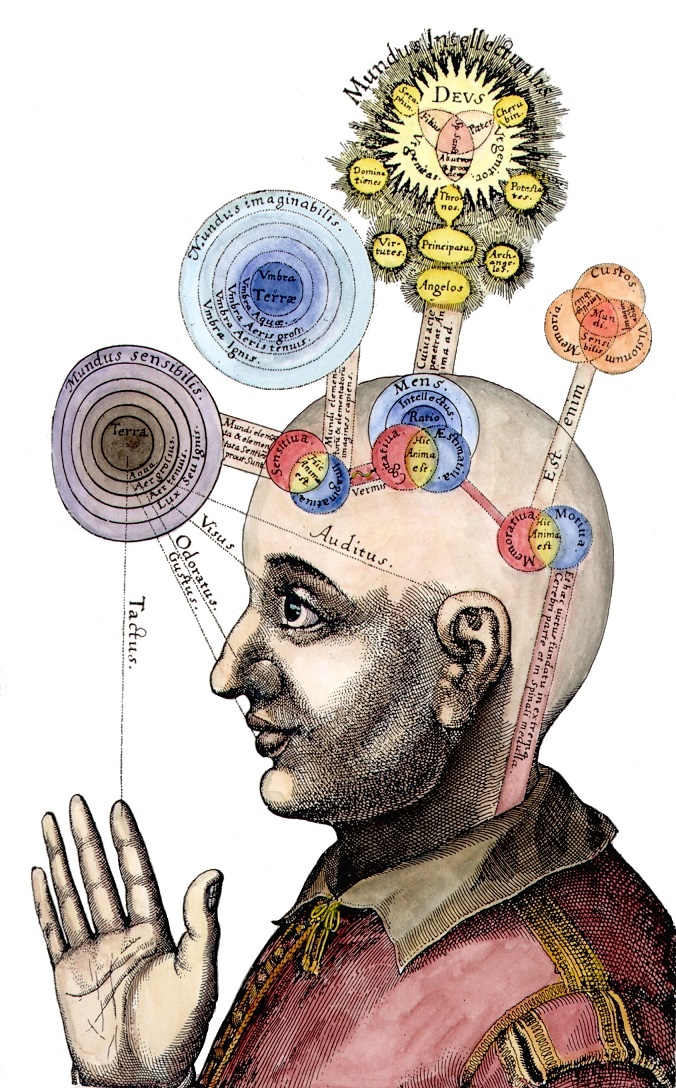

Anomalous experiences may be

conceptual or perceptual in nature; they may pertain to either an ascribed

schema or system of beliefs or to unimodal and/or multimodal sensory

perceptions that arise in a spontaneous fashion in the absence of an appropriate

context and without a corresponding stimulus from the sensory-corporeal world

(Williams, 2012). What is more a standard definition of the word should also

honor the evolutionary purpose served by perceptual mechanisms; if all conscious perceptions are, in fact,

cheap and quick guides to adaptive behaviors in environmental niches then the

anomalous ones amongst them could also be conceived as perceptual constructions

which are not adaptive guides to behavior (Hoffman, 2012).

Phenomenal content in conscious

awareness that is not adaptive is bound to be atypical, discontinuous,

incoherent, and irrational. Indeed, anomalous experiences are diametrically

opposed to integrated perceptions and frequently manifest as disassociations or

fragmentations of consciousness, the splitting of cognition from affective

aspects of experience, and powerful affective fluctuations manifesting

phenomenologically as polarized expressions of good and evil, omnipotent

control and helplessness, creative and destructive forces, heroic striving,

groundlessness, and parallel dimensions. More often than not feelings of

euphoria, liberation, and interconnectedness are also present (Williams, 2012).

Positive internal appraisals of this content [or non-distressing anomalous

experiences] attract to themselves the label of “spiritual” whereas negative

ones that are significantly distressing and ensue in intellectual,

interpersonal, social, and occupational impairment are pathologized and deemed

“psychotic” under the hegemony of the biomedical model and the Western mind

sciences (McCarthy-Jones, 2012).

Some anomalous experiences like

autoscopic phenomena, multimodal hallucinations, and synaesthesias may be

conceptualized within the dominant, existing scientific model. Other anomalous

experiences like extrasensory perception, anomalous photography (the mind’s

ability to influence photographs), levitation, teleportation, and bilocation call

for a steadfast revision of the Cartesian-Kantian epistemological box couching

the unidimensional model of time, as well as standard notions of a

materialistic universe. Others still, for example reincarnation-type

experiences/past-life memories, out-of-body experiences (OBEs), near-death

experiences (NDEs), drop-in communicators, and séances involving proxy sitters,

undermine the conventional product model of mind-brain that cognitive

psychology and cognitive neuroscience are predicated on.

Theoretical

models congruent with contemporary mechanistic science have occasionally been

propounded to account for them, despite their subsistence near or outside the

empirical frontiers of eliminative materialism. For instance “Weak Quantum

Theory” posits that anomalous “psi” experiences and veridical past-life

memories occur because there is an entanglement of nonlocal minds in a latent collective

unconscious (Health, 2011). Others, like teleportation and apports, are qualitatively

closer to phenomena we see in science-fiction and so incongruent with the

materialistic agenda of the hard sciences that no explanatory model exists or

has been proposed to account for them. Collectively, anomalous experiences

illuminate the gaping fissures, the obvious inadequacies of our dominant albeit

myopic worldview.

References

Cardeña,

E. E., Lynn, S. J. E., & Krippner, S. E. (2000). Varieties of anomalous

experience: Examining the scientific evidence. American Psychological

Association.

Hoffman,

D. D. (2012). The construction of visual reality. In Hallucinations (pp.

7-15). Springer New York.

Pamela

Rae Heath, M. D. (2011). Mind-matter interaction: A review of historical

reports, theory and research. McFarland.

Warwick,

S., & Waldram, R. (2010). Exploring the Transliminal: Qualitative Studies. Psychosis

and Spirituality: Consolidating the New Paradigm, Second Edition, 175-191.

Williams,

P. (2014). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding

and treatment of psychosis. Sky’s Edge Publishing.