Christmas has always been a season infused with the spirit of anticipation, as well as the mutual exchange of well wishes and presents. Then there are those oppressively opulent Christmas lunches and dinners in which the vast majority of partakers gorge themselves as if it were their last day on earth and spend the next three weeks nervously evading the bathroom scales and wondering why they did it. All too often a lack of restraint and conditioning is reason for one to curse the very celebration he or she had embraced with fervour only days ago. It goes without saying that for our children the experience of Christmas is vastly different; the senseless and meaningless complexities of the ego haven’t quite developed yet, the burden of responsibility is altogether absent and the essence of their being is faithfully entwined around a pole of endless feasibility. Nothing and nobody ever befuddles children in their creative moment of imagining and role-play, two endeavours that imbue the cosmos with meaning and purpose and is almost always jettisoned or lost when one sheds the skins of childhood.

When I was a youngster, I remember waking up to the pungent scent of sliced bread being roasted in the toaster and the sight of numerous Christmas presents underlying the tinsel-laden and star-crowned Christmas tree in the lounge room. Those were the days when I was mortified by gruesome, malevolent creatures that went bump-in-the-night and slipped through dimensional portals to escape into fantastical worlds when reality seemed bland and lacklustre. Those were the days when I searched frantically for the tooth fairy that left me money in a drinking glass as a reward for having shed my first teeth, when I tiptoed into the lounge room on Christmas Eve expecting to catch Father Christmas in his philanthropic act of scattering presents beneath our tree, and when assuming the role of evil characters from fairy tales and stories was an avenue that led to the enchantment of Mother Nature herself. Everything was novel, sacred, holy, magical, enchanting, and mystifying even. Sometimes I’d like to think that I haven’t lost that spring-morning magic; my childhood wand is still about, perhaps in a green leather chest somewhere in the old basement. All I need to do is find it.

I remember, quite vividly in fact, the spirit in which we celebrated Christmas in my early years. What made the season soulful and endearing wasn’t the idea of scrumptious and lavish banquets or presents or the notion of Father Christmas descending into our residence from the charred conduit above the fireplace. It was the many stories told by my charismatic grandmother about a species of menacing goblins called the kallikantzaroi who emerged from their subterranean lairs during the twelve days of Christmas in order to wreak havoc and lead the unassuming among us ashtray. For me, the foreboding presence of demonic minions and their subsequent running amuck during the same period in which the anniversary of the birth of the Son of God was celebrated seemed contradictory to a degree, and on the hand, well, enthralling.

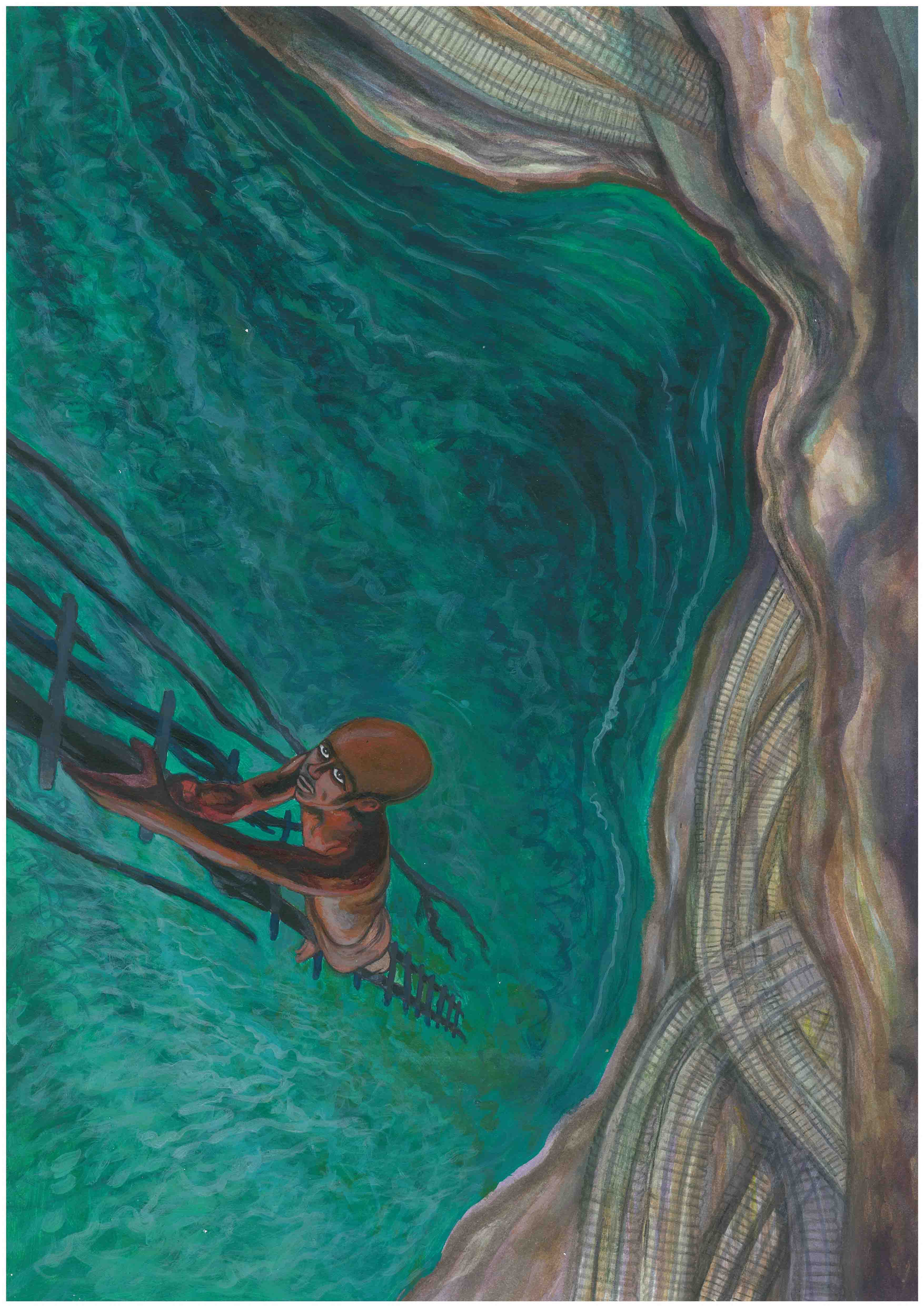

As far as mythographers, folklorists and historians are able to discern, the folkloristic tradition relating to the kallikantzaroi are an entirely Greek and Turkish affair. Belief in them was rife in the Hellenistic lands during the Ottoman Occupation, and it appears likely the tradition subsisted amidst rustic consciousness well into the twentieth century. Kallikantzaroi were held by most Hellenes to be the spawn of evil. They thrived deep inside the dark, moist womb of the earth and when not in a state of slumber busied themselves by gnawing at the trunk of the Great World Tree. Their collective ambition was to annihilate the human race by undercutting enough bark from the axial giant as to topple the cosmos. Legend has it that their task neared completion in late December, a time at which the ethereal gates bridging different dimensions would be flung open and allow intermingling between different orders of beings. The gates would remain open between Christmas day and the festival of the Epiphany on the fifth of the New Year, allowing the kallikantzaroi to bring their duplicitous, mischievous and homicidal reign of terror to the Earth. On closer inspection their mingling with human beings wasn’t an altogether lamentable affair; their temporary absence from the subterranean was humanity’s saving grace, for it allowed the bark around the trunk of the World Tree to regenerate and thus continue nourishing the three tributaries of the cosmos–Heaven, Earth and Underworld.

Just as we have UFO enthusiasts nowadays reporting variant species of extra-terrestrial visitors so too were the rustics of Greece proper convinced that there were two distinct classes of kallikantzaroi, each with their unique physical characteristics and temperaments. The first were about two metres in height, lean and powerfully built, and resembled the ape-like American cryptid Bigfoot. The list of physical characteristics appears to vary from place to place, though most are in unanimous agreement that these types possessed horribly deformed faces, translucent red eyes and tongues, black skin and shaggy hair, the ears of goats or asses, the arms of monkeys, razor-sharp talons, and protruding horns. They were also equipped with oversize heads and penises. A great many were lame. Their vile physiognomy was matched only by their tasteless pranks as well as their heinous and murderous intent. These types prided themselves in their ability to suffocate their human victims by sitting on their chests whilst they slept complacent in their beds or alternatively strangling them outright, slashing their throats open and then gulping down their oxygen-rich blood. The second variety was scanter in number, shorter in stature and stayed faithful to anthropomorphic forms; most tried to imitate healthy six or seven year-old children but differed from the former in that they exhibited smooth, blackened, and sometimes putrefying skin in addition to a horde of other physical deformities. It appears that these smaller types were frivolous, boisterous and somewhat innocuous when juxtaposed with their much larger cousins. Chief amongst their concerns was the incitement of pandemonium and the widespread promotion of social disintegration.

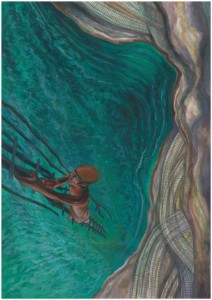

Like a great many other mythological creatures or xotika of Hellenistic folklore, the kallikantzaroi were confined to a nocturnal sphere of influence that commenced at dusk and ceased at daybreak. Because direct sunlight would blind them and subsequently render them dust, the daytime hours were spent reposed in the dark recesses of caves or windmills. A kallikantzaros might bide his time ruminating about how many households he can bring ruin to in one night, swimming in subterranean rivers or feasting upon snakes, salamanders, lizards and other little reptiles to rejuvenate his energies. During this time the rustic population were raising what they believed to be incumbent prophylactics to ward off these nocturnal attacks. Many people would resort to nailing large crosses or the lower jaws of a pig to their front doors, drawing figures of black crosses on the main archway of their residences or burning frankincense and myrrh in an attempt to keep the demonic intruders out. Others used methods quintessentially pagan in character, like hanging bits of thistle, asparagus or hyssop on the chimney or outside the door. It is alleged that kallikantzaroi were cantankerous, stupid and largely void of common sense, so to dupe them all one had to do was leave a sieve or a bundle of flax on the front porch. Given the ephemeral nature of their concentration the implements would serve as enumerative distractions, keeping them busy until the crack of dawn whence they would be forced to drop everything and flee.

It was believed that kallikantzaroi feared fire and encompassed an inherent aversion towards black roosters, hence townsfolk made every attempt to have one or both around. Fire proved to be a formidable ally, for it fortified a part of the house (i.e. the chimney) that would have otherwise granted easy access to the would-be intruders. During the twelve days of Christmas householders would keep the fireplace going unremittingly and leave the ashes of the hearth untouched. Following the purification of waters that typified the ritual of the Epiphany–a time also believed to signal the return of the kallikantzaroi to the Underworld–the head of the house would round up the ashes, now endowed with magical properties owing to a presumed interaction with the supernatural beings, and disperse them over his crops to facilitate good produce. In the case that one or all of these prophylactics failed and one came face to face with a kallikantzaros during the twelve days, he or she was advised to disregard their senseless banter and only open one’s mouth as to recite prayers and incantations. Kallikantzaroi were like the Nereids; once their presence was acknowledged, their powers multiplied and they were able to exercise a definitive influence over the individual. Another didactic piece of traditional anecdotal literature advises that the first question a kallikantzaros is bound to ask any innocent bystander is, ‘Will you have tow of me or lead?’ to which the one-word response ‘Tow’ should be given. The latter renders the malevolent forces impotent.

Some of the anecdotes told about their level of foolhardiness make for lively home entertainment, especially during the festive year-end season. One which has remained with me through the years is the story of how a beautiful young woman was able to evade the Machiavellian intent of a little kallikantzaros. On Christmas Eve, or so the folktale narrates, the woman stayed at home for the sole purpose of preparing a late night dinner whilst her husband and children attended mass. After a short while she became acutely aware of something flitting about behind her. Pivoting on her heels she came face to face with a blackened misshapen child that seemed to mutate before her very eyes. The woman knew intuitively that she was in the presence of a kallikantzaros. It proceeded to scurry about on all fours like an arachnid, laughing hysterically and defecating everywhere before granting her his undivided attention. “What is your name?” the creature asked. Mindful of all that had been imparted about these flippant but dangerous goblins, she replied “I, myself”. The kallikantzaros went on scampering about and upsetting furniture, intensely fascinated and absorbed by its own ability to break and tear things until the woman finally mustered enough resolve to launch a counterattack. Angered beyond reckoning, the woman took a sweltering saucepan off the stove and hurled it at the kallikantzaros, striking him just below the jaw. The creature yelped out in pain and rushed outside into the somnolent darkness, eager to show the burn to his fellow peers and gain widespread support. When the small kallikantzaros was prompted to disclose the identity of the individual who had committed this atrocity against him, he blurted out, “I, myself.” The group broke out in a cacophony of laughter; some mocked him, others poked and prodded him. In the end the consensus was that he had behaved like an imbecile and was hence undeserving of any pity. In this way the young woman evaded any wrathful retaliation on their part and lived to tell the tale.

Another tale, this one indigenous to the island of Skyros in the Sporades, speaks of a young man who ran into some wandering kallikantzaroi whilst returning home from the mill one night. His gut instinct was to stretch himself out between two sacks of wheat on his mule’s back in the manner than ‘planking’ enthusiasts prostrate themselves almost everywhere nowadays. To complete the façade he blanketed himself with a pleated rug as to fuel the illusion that he was just another sack of wheat. By their very exposure to the rustic lifestyle, the kallikantzaroi had learned that wandering donkeys and mules were usually accompanied by human masters. Soon they had congregated around the mule, examining the load on its saddle and pulling its reins some. “Hmm…,” one of them muttered, “there’s a sack of wheat on either side of the mule, and an even bigger one in the middle! So, where’s the man gone?” The kallikantzaroi attempted to solve the mystery by either backtracking to the mule’s place of origin, the mill, or venturing on ahead, frequently returning to the animal to vocalise the same concern but all to no avail. Riddled by this question of how the mule’s master had dematerialized into thin air took up just enough of their time for the man to arrive home unassailed.

Before the heinous goblins could recover their wits about them, the man cried out to his wife for immediate assistance. His wife hurled opens the door and within seconds he and his bags of wheat were reposing inside the haven of his own home. Realising at once that they’d been duped, the kallikantzaroi marched up to the front porch and thumped furiously on the door. His wife, the shrewder of the two partners, was quick to act; she appeared at the window near the door and told them that if they could correctly enumerate the holes in her sieve she would grant them entrance without any objection. Oblivious of their own intellectual incompetency in arithmetic, the kallikantzaroi hastily accepted her challenge. Elated at this the woman suspended the sieve from a cord and lowered it to them from a high window. They snatched it up and proceeded to count, but before reaching double figures they became puzzled and had to start over again. Their tribulations went on and on and on, until first light appeared and they had to flee.

Remarkably the origin of this folkloristic belief remains shrouded in obscurity. In examining the physical and temperamental characteristics of the kallikantzaroi along with the prophylactics aimed against them one is bound to find parallels with the traditional lore surrounding the Greek vampire and the Greek Nereid. Crosses, pigs’ heads and herbs, for instance, were also used to ward off beings of many different natures in ages bygone and the notion of denying a supernatural entity power through the purposeful observance of silence extends to nearly all classes of xotika. Variant hypotheses have run the gauntlet for the purpose of gaining conventional acceptance, yet none have fully succeeded. The view, for example, that kallikantzaroi are an archetypal projection and personification of night terrors has been criticized as being a simple and one-dimensional view, dismissive of the fear they were able to strike in the collective psyche. A much more viable perspective has been offered by folklorist George. A. Megas, whose academic opinion gravitates around the idea that the goblins are a memotype relaying the ancient eschatological belief that Pluton would fling open the gates to the Underworld for the temporary liberation of deceased souls on a day of the year celebrated as the Athenian festival of the Anthesteria. HIs impression would have been more than satisfying had it not been for the calendrical incongruities between the two events.

Perhaps the most curious approach is that of Bernhard Smith, who chooses to descry an origin for the kallikantzaroi based on the etymological route of the name itself. He argues that the word for the goblins is comprised of two Turkish route words which mean ‘black’ and ‘werewolf’, inexplicably linking the tradition to the shape-shifting transformation of a man into a wolf known as a lycanthropos. This notion acquires an even greater viability when one takes into account the shared traits between the two supernatural entities and the propensity of the Peloponnese rustics to use these two terms interchangeably in describing the Christmas goblins. Despite its feasibility there’s one other theory which issues a much sounder note on the historiographical scale and overshadows the abovementioned completely. Put forth by Nicholas Polites the model identifies the kallikantzaroi as the collective memories of a pagan festival of the winter solstice that was celebrated in antiquity under the aegis of the Chronia and the Dionysia and involved dressing up in costume, drinking oneself into a stupor and behaving in frivolous and counterfeit ways. For Polites, the kallikantzaroi are nothing more than psychic interpolations ensouled by themes and images belonging to a primordial pagan masquerade.