According to cognitive neuroscience the brain and its supporting tissues are the corporeal embodiment of the mind; without it all higher mechanisms of causation including consciousness, language, imagination, and memory would not be possible. In fact, we could probably narrow down our ability to function and form complex levels of interaction with our environment to three specific factors: the evolution of the cerebral cortex; the configuration and organization of neural subsystems within the brain; and the gradual development of cortical networks like the prefrontal and polymodal cortices of the formative brain which enables cultural factors like societal norms and conventions, religion, and psychospiritual belief to enact dynamic influences upon the concretization of functional neural networks. To understand how this all transpires we need to take a brief look at the human nervous system and how it processes information from the phenomenal world.

From a simple and elementary perspective, the nervous system is an efficient self-regulatory and meaningful mechanism that measures the consequences of actions enacted against intended outcomes and adjusts all motor activity accordingly for the sake of achieving those outcomes. In this way, it works diligently and tirelessly in delimiting the range of possible interactions in the environment that are most likely to garner biologically and psychologically-relevant goals. Scientifically, such a phenomenon is known as an action loop and best possible way to understand how these operate is to proceed with a tangible and specific example. Let’s shift our attention to the African wilderness for a moment, a place where the predator-prey relationship forms the crux of a planetary ecosystem delicately balanced between the forces of creation and destruction. Here, it’s not at all uncommon to witness lionesses trying to assail herbivorous behemoths many times their own size and physical strength. Hypothetically speaking let’s assume that a quartet of lionesses initiate a nocturnal attack against a giraffe. The violent bottom-up assault which ensues manages to inflict a sequence of major wounds and abrasions on its hindquarters but falls a little short of levelling it.

In light of the action loop, the basic instinct to survive is what prompts the lionesses to attack and kill another living animal; their inability to throttle its neck by levelling it to the ground is the sensory feedback received from the conformation of the encounter; and the subsequent juxtaposition of the result with the intention to successfully assail the giraffe spurs a modification of their actions that involves calling to arms additional team players like young males or the proud chief of the pride himself. Thus, the next time around the authoritative lionesses will proceed with a far more meaningful, innovative, and coordinated plan of attack than the preceding one in which the intended outcome was not realized. Of course the action-feedback (sensory-motor) interactions of the human nervous system are a lot more intricate and convoluted than anything that might unfold in the African wilderness, but the dynamics are still the same.

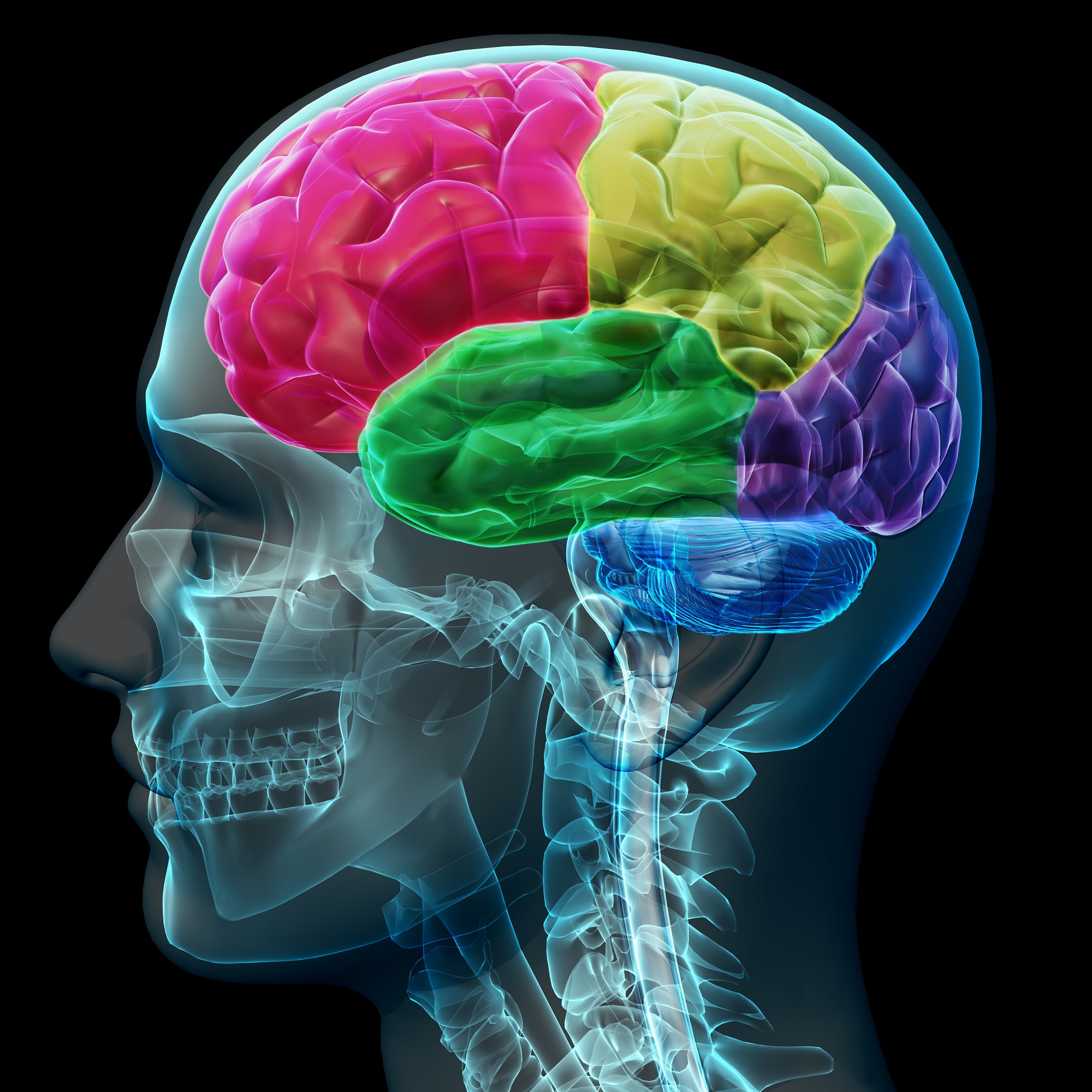

As a general rule of thumb sensory-motor interactions are not monolithic or one-dimensional by any stretch of the imagination. In actual fact, by looking at the Central Nervous System (CNS) as a whole it becomes clear that complexity and sophistication of modulation varies according to the hierarchical order of the neural structures and substructures contained within it. Logically then, the action loops associated with the spinal cord, the neural matter which relays information from the skin, joints, and muscles to the brain, are the least complex and those of the cerebral cortex, the slice of grey matter beneath the surface of the cerebrum, the most complex. Squashed between them in ascending order of intricacy are: the brain stem, a node of fibres which conveys information between the cerebrum and spinal cord and regulates breathing, body temperature, and consciousness; the midbrain or mesencephalon, a portion involved in vision, hearing, control of movement, and temperature control; the diencephalon, an autonomic function centre of the peripheral nervous system between the cerebrum and the brain stem; the thalamus, a part of the diencephalon (and forebrain) interconnected with the cerebral neocortex and associated with sensorimotor signals, alertness, and sleep; the cerebellum, a movement control centre connecting the cerebrum to the spinal cord; the cerebrum or telencephalon (part of forebrain), a structure differentiated into symmetric left and right hemispheres; and the cerebral cortex, the highest-level functioning neural system in which sense, perception, voluntary movement, and higher cognition converge. Control and modulation of action loops belonging to lower-level systems are couched within higher-level ones, drawing all sensorimotor interactions of the nervous system into a nested control hierarchy that resembles the socio-political pecking order of contemporary Western society.

Critical to this investigation is the central eminence of the cerebral cortex in which there is a conversion of modulation and action loops belonging to all other dynamic neural systems. At this junction, areas involved in sensory processes and motor input amalgamate with specific sensory and motor processes in addition to the polymodal sensory processes taking place in the posterior cortex. All this enables an individual to enact the sophisticated feats that have enabled civilization to evolve and have established culture and tradition as unique, remarkable expressions of humanness like contemplating, imagining, solving complex mathematical and spatiotemporal problems, and engaging in internal conversations with one’s own self. On the whole, the manner in which the higher-level systems transliterate higher cognition from the nested lower-level systems is overly complicated and extremely difficult to comprehend when one’s knowledge of cognitive neuroscience is marginal and so the most fitting and comprehendible explanation in this case might also be a metaphorical one.

Imagine that the cerebral cortex is a high-tech Sony video camera and that the lower cortical-sensory and motor-control systems falling under its mediation are a dreamy landscape of mountains, forests, rivers, and lakes on which events are continuously unfolding. The camera in question is powered by an inexhaustible power supply and is always switched on, recording every bit of detail, action, and motion in the terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial realms. It can zoom in and out, and it can operate on widescreen or full screen mode. In its allegorical guise of video camera, the cerebral cortex can rerun sections of digitally-taped film on the projector screen of your own home (or the space inside your head) at any time without any assistance or accompaniment from the original physical simulation. So if it wasn’t for the latent activation of cortical-sensory apparatuses by the prefrontal cortex which can rerun snippets of corporeal events there would be no way that one could remember such things as bathing in the waterfalls of Yosemite National Park, fighting with another work colleague over an unprecedented job opportunity overseas, a passionate encounter with a total stranger in an abandoned warehouse, or perusing the giant clams at Hardy Reef off the coast of central Queensland. By the same token the initiation of latent intercourse between the frontal cortex and the cortical-motor systems on which the former piggy-backs allows for vigorous internal conversations with subpersonalities and aspects of one’s own being, inwardly-turned explorations of future possibilities regarding career opportunities and education, and mentally constructing and reconstructing real or imagined altercations with people notorious for their propensity to exasperate others.

Most of the evidence supporting the localizationalist model linking mind and brain comes from nineteenth and twentieth century phrenological experiments involving laboratory rats, monkeys, and humans. A great many of these have succeeded in localizing behavioural and cognitive functions to neural structures of the brain. In our time, the invention of less invasive forms of investigation like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has enabled scientific research into the neural mechanisms of consciousness to continue unfettered by such moral and ethical dilemmas that surround the utilization of live animals in laboratory experimentation. Thanks to the conclusive findings of this research, we now know that both the basal ganglia and cerebellum are associated with the motor control of behaviours; the former is explicitly orientated towards amplitude and speed whilst the latter towards timing and coordination. The hypothalamus, on the other hand, incorporates somatic and visceral motor responses depending on cerebral requirements.

One area of mentation much more difficult to pinpoint is emotion, and the intimate involvement of the limbic lobe, the hypothalamus, and the neocortex in emotional value elicits the reality that some conscious human activities and mental states are transcendent products of dynamical system collaboration rather than localization. Of the just mentioned, the hypothalamus is also causally linked to aggression. Situated in the temporal lobe, the amygdala is associated with fear and anxiety. Alternatively the hippocampus is accountable for the processing and consolidation of declarative memories, or memories garnered from facts and events. Recognition memory or the acuity to discern whether a particular stimulus is familiar or not is ascribed to the diencephalon. Language is associated with the left frontal lobe, and particularly Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas; the first with the production of fluid speech and the second with the comprehension of spoken words. Finally, the flat bundle of neural fibres known as the corpus collosum is critical to intercerebral communication between the two hemispheres of the brain and the unification of self-awareness. In perusing enhanced activity of neural substructures with respect to specific human behaviours and cognition, it becomes increasingly clear that the hierarchical and compartmentalistic order prevalent in the brain’s action loops and anatomical functions is reflected by the mind which forms culture and religion in its image.

Another area of research in support of the brain equals mind hypothesis comes from split-brain studies in which the interaction between the left and right hemispheres and their individual natures are examined. The technique involves opening up the patient’s skull and surgically disconnecting the corpus collosum, the bundle of axons connecting the two hemispheres, and then probing to see if there is any discernible effect on intercerebral communication. Results from carefully devised visual experiments have thus far revealed a bifurcation of self-awareness and a loss of wholeness. When “split-brain” patients were carefully positioned so that the trajectory of vision pertaining to each eye could not be altered, images, pictures, words, and objects placed to the left of a point in space were perceptible only to the right hemisphere. Likewise those placed on the right were perceptible only to the left hemisphere.

Split-brain studies also demonstrate hemispheric asymmetry when it comes to verbalization of language, a phenomenon which corresponds well with the notion that language is dominant in the left cerebral hemisphere. Anything presented in the right visual field or placed in the right hands of these patients could be accurately verbalized and described but when the same stimuli were presented in their left visual fields or placed in their right hands the patients could neither sense nor perceive it. Even though the right hemisphere could not express itself verbally, the results garnered showed that it embodied all requisite mechanisms needed to understand language. Further it appears the right hemisphere was much more capable than the left when it came to replicating three-dimensional pictures and figures; at solving riddles; and at discerning auditory nuances. Subsequent in-depth studies have shown that the two hemispheres exhibit conflicting behaviours whilst trying to solve the same problem, a conjecture which indicates major differences in the modes of reasoning utilized by each. What all of these incongruities between the two hemispheres seem to suggest is that two minds and two brains co-habit the human body.

We have thus far established that complex interactions in the brain mediate behaviour and cognition but could we go as far as to suggest that conscience is rooted in neural mechanisms? Is morality, the ability to make moral decisions that encompass certain consequences, also mediated by the neural makeup of one’s frontal lobes? One explicit case that hints at the existence of a corporeal embodiment for conscience is the renowned and lamentable accident of Phineas Gage. Gage, a twenty-five year old railroad construction foreman, was involved in an explosion whereby a six kilogram tamping iron rod ripped through his head, entering just beneath his left eye and exiting out through the top of his skull. Save for losing profuse amounts of blood, the injury cost Gage much of his skull and left frontal lobe, the latter being a highly evolved area of the brain which acts as the executive administrator of behavioural processing diffused across other neural subsystems. Gage miraculously recovered from his wounds as well as an ensuing infection that nearly cost him his life, however his personality was perpetually altered for the worst.

From a shrewd, intellectual, determined, focused, and well-balanced industrious specimen of the human race Gage became chaotic, impertinent, impulsive, and obstinate. Those who either knew him well or had made his acquaintance unanimously declared that he was no longer the same personality after the harrowing accident. Somehow, the severity of the damage to his frontal lobes unhinged the moral patina layering the man’s intellectual makeup which had the adverse effect of plunging him back into a prepersonal confluence of irrationality and untempered emotions, a place where the container of the ego hasn’t yet been infused by direction, gravity, or focus. His unfortunate incident demonstrates that the neural mechanisms of the brain might embody greater formative influences upon human conscience (itself an exponent of culture and religion) than what we’re currently prepared to admit.

A final point that should be made about the brain relates to its genetic blueprint and synaptic plasticity. Barring any prenatal and postnatal defects, the anatomical substructures and their functional associations along with the cortical neural circuits within the skull are genetically predetermined and assume a wrinkled form which is identical in all human beings. The only region where some expression of individuality might be seen is the cerebral cortex. Despite the fact that the environment plays a significant role in the density and intricacy of cortical circuits, the general depth and breadth of one’s intellectual capacity or intellectual potentiality is inherited. Thus you could probably thank your parents for your cerebral acuity or blame them for your lack thereof.

At any rate the first few years of life are characterized by the generation of long-range synaptic connections and axonal pathway formations by differentiating neurons. The brain resembles a sponge at this stage and the particular configuration of interactions with the phenomenal world shapes the general framework of synaptic arrangements and dendritic nerve branches. Neurons fire and wire together in accord with the trajectory of experiences and learning acquired during an individual’s formative years. During this critical period of development, the sensory environment is instrumental in trimming and refining all proliferating dendritic branches and synaptic connections that become inert or are not in synch with the nexus of self-organizing neural networks. While the critical period for axonal pathfinding and synaptic connectivity in the CNS constricts and pinches out rather quickly, those of the higher dynamic neural subsystems like the prefrontal and polymodal cortices remain robustly plastic with respect to cortical thickness and axonal myelinisation well into early adulthood. The slow maturation of their cortical circuitry, a phenomenon which involves the creation of new synapses or modification of protein synthesis and microcircuit assemblage at existing ones, enables experience-dependent memory to form and effectual learning to take place over much longer periods of time. Hence transpersonal influences that originate as folklore, myth, religion, and tradition together with the formative contents of consciousness like thoughts and imagination can all explicitly modify and influence the concretization and final organization of neural mechanisms within the brain.

In hindsight, cognitive neuroscientists have made ample use of past and present experimental literature seeking to localize cognitive function to specific areas of the brain and the hindered maturation of the cerebral cortex to build a compelling argument for a neurophysiological basis of human consciousness. Using fMRI techniques to link up enhanced neuronal activity in brain subsystems with forms of higher mentation like praying, reading, and the experience of transcendental visions or mystical states (i.e. the identification of the “God-spot”), neuroscientists can argue that the evolution of our personal sense of self–a multidimensional stream of mental life able to form abstract and symbolic representations of embodied entities and to communicate through spoken language–is a developmental and learned achievement that we can attribute to the receptivity and plasticity of our brains in “bending” to perpetual vicissitudes in the environment. From this angle, the “I” that sways to the ebbs and flows of half-formed desires and emotions; the “I” that hopes to understand others and be understood; the “I” that wants to be validated and to gain consensual acceptance in a world that can at times appear as alien and inhospitable as the sulphurous fumaroles of volcanic mountains; and the “I” that yearns for happiness and contentment is the highest gear, the fifth, in a highly complex, dynamic, and superdense vehicle that is your cerebral cortex. When this vehicle switches to a lower gear or breaks down completely, the “I” dematerializes and vanishes into oblivion…

Or does it?