Transcribing private thoughts onto paper is undoubtedly one of the most sacred art forms known to humankind. The act of putting words onto a blank slate not only presupposes a changing interpersonal dynamic between an individual and her social environment, but implicitly suggests the existence of an ongoing intrapsychic discourse of the personal self with a silent, unbeknownst audience often conceived as an idealized, higher, or objectified version of that self. And why would we spend hours if not days, weeks, months, and sometimes years writing, rewriting, and revising our words? Simply because we’re trying to orientate, acclimatize, and fit into an ever-fluctuating world of shadows, a world without edges and demarcations, a world indifferent and insensitive to the emotional ebbs and flows of our Precambrian-flavored mental life. By resorting to the pen instead of the sword, we might also be trying to rationalize a negative emotional insurrection within our inner kingdoms which has been generated through some external agency like the sudden loss of a romantic relationship, the death of an immediate family member, or the unprecedented termination of employment. Lamentably so, misfortune and meaninglessness drives one to the writing desk far more often than what happiness and contentment do.

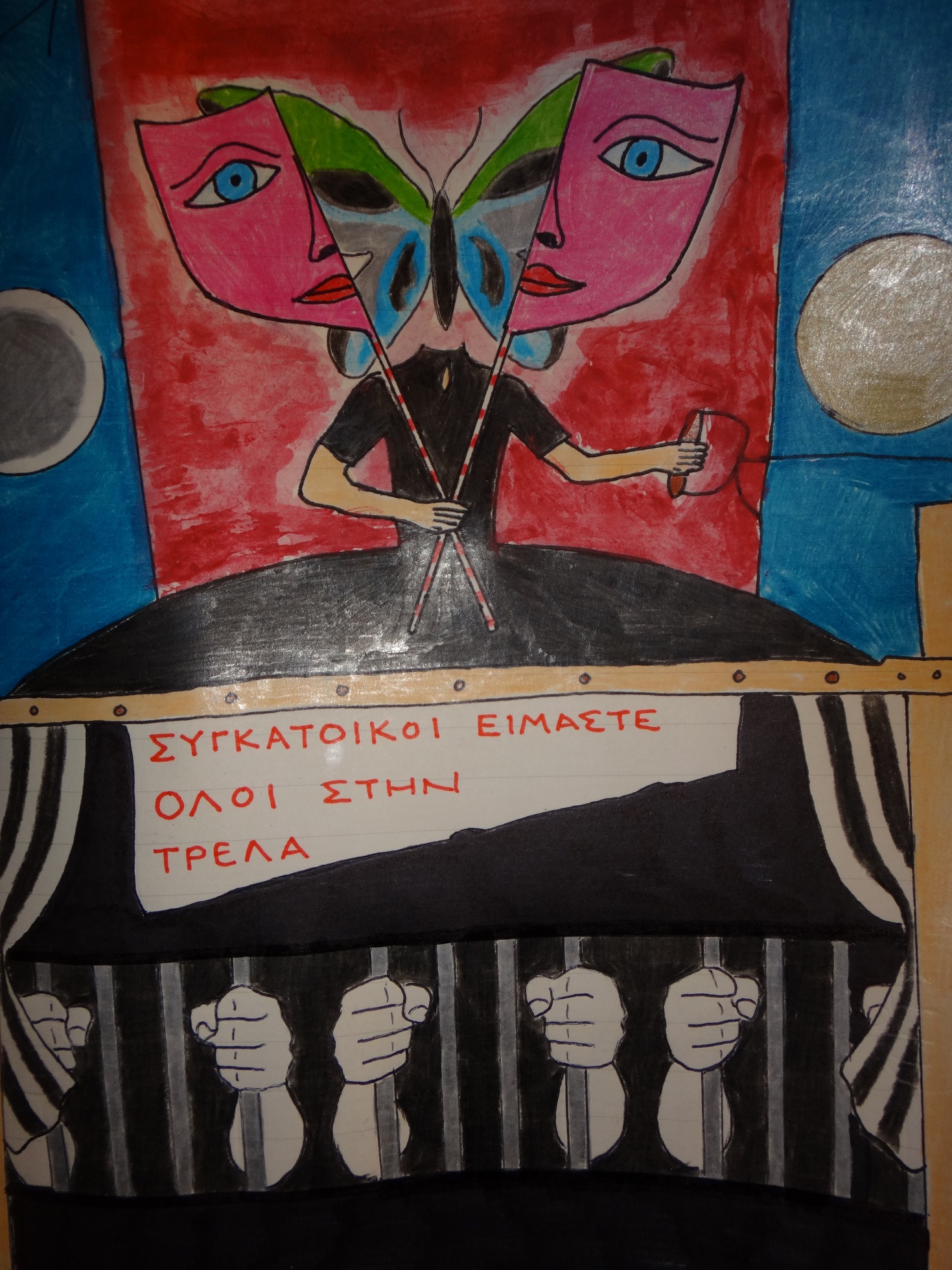

In my mind, sitting down to write a letter or an entry in a journal may be equated to a water nymph venturing under a thunderous waterfall to bathe, a water lily opening up its royal petals at the prompt of the splendid sun, and a white rabbit deserting the safety of its earthly sanctuary in a sprawling prairie strewn with aerial predators. Qualitatively similar to the aforementioned scenarios, it requires a confluence of naked honesty, reflexive spontaneity, latitude, and undaunted audacity which in many a case renders the writer most vulnerable to discerning eyes full of burning bigotry and judgment. (Of course the latter part of this statement only holds true when we share our personal works with others and publish them.) During the writing process, we are often dialoguing with repressed, disenfranchised, or hitherto unvalued and unknown parts of ourselves, or nonconsciously exposing softer, more pliable aspects normally hidden beneath the superficial horny layer of social skin called the personality, the mask we present to the world. Hence by unleashing them we risk being misconstrued as threatening, duplicitous, and antagonistic by the collective prerogative.

Whichever the case, we can meander about and hide from others using intrapsychic contrivances and even create false selves in an effort to appease and concord with the prevailing status quo, but ultimately there can be no hiding these integral truths from ourselves. Doing so is counterintuitive, counterproductive, and moreover self-destructive because it sets the stage for the unwelcomed proliferation of negative influences in our lives. Whether we wish to admit it or not, bottling up genuine sentiments can put us on a psychic one-way motorway to pathogenic mental states, psychosis, homicidal impulse, and even suicide.

In scrupulously examining the subject of my own collected works as well as the preoccupations of others writers over the years, I have found that individuals are more prone to creative writing (poetry or prose) when they’re confronting those existential issues we have absolutely no control over. We are aware of our transient existence, the fact that we are born into the world fated to suffer pain and to die, so we engage the dialectic in the only way we can–by writing about it. Our left hemispheric interpreter implores us to make personal meanings out of random actions and incidents and contextualize them within a greater autobiographical narrative however the rational and intuitive faculties responsible for these cognitive patterns are constantly undermined by personal and collective tragedies for which no meaning can be wrought. What possible reason, for instance, could justify the heart-wrenching loss of one hundred or so talented children in a mid-air disaster? What higher reason could exist to account for widescale starvation and poverty in Africa while millionaires enjoy lavish and oppressively opulent lifestyles in overdeveloped and industrialized areas like the USA, Europe, and Australia?

Likewise, the finite freedom to make choices with far reaching consequences for ourselves and others troubles us at the deepest and most visceral level, so we respond by exploring possibilities with the aid of creative outlets without having to act them out in real life. Moreover we understand that interfaces between incongruous intrapsychic universes, those loosely held bundles of neurobiological and psychospiritual impulses, frequently leads to rejection and denunciation and makes the social synapse appear ill-disposed, yet we willingly accept these psychological tortures if it means a chance at connecting with another on a wholly empathic and authentic level. Once again, the craft of writing is what makes the latter possible. In hindsight, we see that the numinous human spirit wishes to immortalize itself through the written word at times when it is struggling to come to terms with the four disenchanting givens of existence–death, isolation, freedom, and meaninglessness. Despite its strangeness the paradox is both transparent and fathomable–humans seek validation, meaningfulness, stability, indestructibility, and immortality in a mutable and unruly universe.

Looking back over my own autobiographical history the one thing standing out like a sore thumb is a dark day in my early teens when I underwent a strange malady of unknown origin. It came on gradually, perhaps over the course of a week. I woke up one morning feeling somehow not myself. Suddenly, things didn’t feel right within me anymore. I didn’t feel well within myself. There was a wrongness where prior there had been none. Something had changed. I couldn’t put my finger on it; I didn’t know what it was—how could I? There was no tangible physiological measure able to describe the intrinsic qualities precisely so that it could be grasped by others and by the contemporary medical intellect. Nonetheless I gaged its presence because my phenomenal subjective state and inner life had been qualitatively different before its manifestation. If I’d been born this way I would have been completely oblivious of the fact; illness is a relational concept that can only be understood when the atypical mind-brain-body states believed to embody it are juxtaposed with a consensual prototype of psychological and somatic health. Entities not normally part of oneself reveal themselves through relation.

In the decade that followed there was an intense preoccupation with discovering an etiology for a nexus of polymorphous symptoms that included muscle fatigue, exhaustion, photophobia, depression, and neurosis. Just as the moon is subject to the cosmic cycle of waxing and waning, so too did my agonizing symptoms undergo periods of alleviation and worsening. These, it seems, were all intimately entwined with a deep-seated intuition that something uncanny was unfurling within me, something for which modern medicine had no feasible explanation. Little by little feelings of disillusionment with medicine and the domineering obsession with discovering the truth tore me from my existing web of interpersonal relations, and I withdrew from the social synapse into a spectral space of utter isolation. Was I suffering from an unknown neuropathology, something Newtonian-based medicine had yet to encounter? Was I standing at the treacherous precipice before the onset of psychosis? The answer to those questions still eludes me, and I often submit to the reality that I may pass over without having disentangled the fundamental Gordian knot of my life.

At any rate the polymorphous condition unleashed intense periods of self-absorption, self-reflection, and creative writing. Creative illnesses transcend sociopolitical and religious frontiers and are actually quite common across cultures and epochs. These phenomena seem to be especially prevalent among shamans, philosophers, and writers. After an unusual neurosis that lasted between 1894 and 1900, Sigmund Freud emerged into the intellectual and scientific world with an inspired perspective on unconscious life, enabling him to write his celebrated The Interpretation of Dreams. Similarly, Carl Jung underwent a creative illness between 1913 and 1919 which motivated esoteric works like the Red Book, the Black Book, and the Seven Sermons to the Dead and laid the humus for the sprouting of theories surrounding archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the actualized Self. I, too, spent a great deal of time deeply preoccupied with the mysteries of the human soul, and emerged from my ordeal in an exhilarated state. The latter culminated with a three week period of incessant writing where I transcribed my screaming Shadow (to use a Jungian term) onto paper. Most of the poems written during this stretch were published in Fifty Confessions (2009), probably my most personal poetic collection to date.

Roughly five years after having published this confessional work, it has dawned upon me that the poems therein were unconscious irruptions attempting to rationalize the relentless pain and suffering, and more significantly, place it within the larger context of a meaningful world with teleological propensities. Rarely will the ailing human choose a blunt, black-and-white truth suggesting meaninglessness over an idealistic, colorful falsehood full of feel-good narratives and inflated, myth-making heroics. When bequeathed the opportunity to choose our choices reflect proactive and intentional meaning-making through narrative. Such is the need to preserve inner harmony and faith in our lives. This axiom definitely rings true in my case since somewhere deep in the recesses of my unconscious mind a vast, quixotic idea began to flower; the illness wasn’t something physicians, neurologists, immunologists, and psychiatrists could shed any light upon because it was supernatural in origin, imposed by a higher order of spiritual beings as a way of instigating inner transformation and reconnecting me with a grandiose truth about humanity which I alone had to reveal. Vanity, narcissism, and self-importance had to come into it somewhere, right?

This fantastical overture cropped up in the prologue and epilogue of Fifty Confessions:

Prologue

Belial: Awake oh, Proteus of all ill,

The chaos-being; the demon.

Who changes shapeless form at will

And imperils all brave seamen.

Proteus: I am here, Oh Captain of all dark,

I hear your call to duty,

This ship of pirates I’ll embark

To steal gold hearts and booty.

Belial: Were you aware nine sons of might

Now spread the Word by sea

A ploy of heinous Aphrodite

To hearten moral glee.

Proteus: She hopes to stamp out your intent,

Your yellowed filth and bile,

Appealed and hoped I would repent,

She thinks me so ductile.

Belial: Take pus and semen from my vein,

And call on our black ravens

To splatter the most lethal strain

Atop their Clay-Do havens.

Proteus: My mind is null,

My hands are bound,

If death is what you wish for;

I chose the heavens as my judge

Twelve stars I called to witness,

That should my silent dagger speak

Against her best, her oldest,

I’d spare the bravest that she’d seek,

Her best beloved, her boldest.

Belial: Make of the clouds your flying steed,

Its reigns you’ll weave

From shark-bite,

Beseech the darkness not to cede

Oblivion to starlight.

Leave these mountains in your wake

And leap the hills; be active!

So hasten for your Father’s sake

To bring that Simon captive

He lives on Hickford Street I know

A house with thorny roses,

Make entrance from the duct below

At dusk when he reposes.

Please blend your seed into his spit,

Be shrewd in blood; be clever,

Then start to take him bit by bit

And swallow him forever.

You’ll find him in his bed tonight,

A child of twelve wee years,

With mother Mary to his right,

Who keeps at bay his fears.

Proteus: I’ll do exactly as you state

Unlike the rest who faulted.

Who went aloof-like through the gate

And found the door well bolted.

Belial: They dropped a rose there

For a hook,

Their plans were not forsaken.

They knocked until

The windows shook;

The brat did not awaken.

Proteus: Fear not, I’ll take that mortal man,

I’ll strike him mute and manic.

I’ll foil their God’s eternal plan

And roust all din and panic.

Belial: Be sure to hunt for Solomon’s key

Which sank in the Pelagic,

They cure ailments by the threes

Through sorcery and magic.

Proteus: A world well void of human trace

Is music to my ears,

Entrust the fiends of our own race

To rouse their morbid fears.

Epilogue

Proteus: Awake oh, Lady of Green Stone,

Awake for news awaits you.

For I have brought you

Flesh and bone,

Your progeny; your children.

Aphrodite: I curse the day

The Lord gave sight

To you, the hidden ferret,

Who razes with your scythe

All night

And quashes my trust;

My merit.

You made a solemn oath to me,

Why won’t you

Keep your promise?

You called our Father

As your judge,

Twelve stars you called

To witness.

That should your silent

Dagger speak

Against my best, my oldest,

You’d bring the bravest

Son I seek,

Where is my ninth, my boldest?

Proteus: Don’t raise your voice,

Oh Aphrodite,

Oh, foam born of Uranus,

For in this jelloid sea of mine

Your Simon sleeps in Silence.

His eyes are lead,

His will runs weak,

In Hades an intruder.

That cunning egregore you seek,

Your Matthew and my Judah.

Apostolos: My mother, it is I, your son,

Your bravest of good measures,

The one you sent so far away

To bring back sunken treasures.

Aphrodite: My son where have your

Good looks gone?

Your dark brown hair all faded?

Apostolos: I fear I lost those years ago

All pallid now and jaded.

Aphrodite: I smell the plot of Proteus

You reek of must; of rile.

Your bloodshot eyes

Your crumpled skin

My beauty they defile.

Apostolos: Have you not heard

A dead man sing?

Not know of living mortar?

For all I yearned for was a spring

To put my lips to water.

Proteus: Forbidden knowledge

You disclosed

In fifty-two reactions,

Confess it all as vengeful lies

And I’ll undo my actions.

I took an oath not long ago.

To thrive in sin and pleasure

And split the silver cords of those

Who surmount wealth

And treasure.

Apostolos: Don’t ask me how

I know, oh fiend,

Such things we must not question!

That felt-tip pen of yours I used

To hasten your detention!

Aphrodite: Your talents are innumerable;

Your will a bar of iron,

But heed my words, oh Proteus

Oh, morbid son of Prion.

I bore nine eagle sons of flight

I have no others for you.

That front of yours

The gallant knight,

I know your ill-intentions.

Do well to leave my sons alone

Or you’ll behold my fury.

It matters not which ones you take

In time they’ll be your jury.

And in the end, vain Proteus,

Behind the veil and curtain.

My Ennead will walk again,

Of that you can be certain.

I’ll raise my children

From the ground,

When roses come to season.

I’ll call on powers dignified

To fill their hearts with reason.

As nine wise men

They’ll rule the world,

They’ll open mind to travel

From deep inside

The caves of earth

Their third eye I’ll unravel

Heed my words, old nemesis,

Oh foremost of Belial;

The mighty Will and Word of God

Cannot be put on trial.

And when the Golden Age

Does dawn

I’ll scry the old world’s stillness,

To prove to you that

The seed and sword

Cannot be crushed by illness.

In hindsight, the unconscious propensity to fathom an enigmatic illness through meaningful contextualization is what delivered me from harm’s silvery and treacherous embrace. On the imaginal plane, it occurred to me that the same pathogen was probably responsible for an unaccountable number of clinical deaths erroneously diagnosed as disorders with a psychogenic or psychiatric origin. On the grounds that I was the pluckiest and most valiant mortal son of the immortal love goddess Aphrodite, I, too, had been selected for imminent extinction by the supernatural agencies responsible for unleashing the ancient ailment to the phenomenal world. Nonetheless the malevolent spirits were quite remiss in gaging constitutional factors when it came to selecting victims for their heinous machinations. My characterological qualities and royal blood rendered me inviolate, and I absconded from its brutal, unforgiving stranglehold armed with a level of empirical knowledge able to induce its demise. Serendipitous, right? Later, a heated dialogue taking place between Aphrodite and Proteus on a psychic plane exposes the aforementioned as a historical chapter and battle to a cosmic war wrought by the formative forces of Love and Death. This further inflates the significance of the illness. Without this spontaneous emanation of creative mental life, the innate ability to make sense out of nonsense, I would have surely capitulated to clinical depression, psychosis, and perhaps even suicide. As Pertinax once said, “Unless you have something to live for, you die before your time.”

Speaking from personal experience, there are times when imagery wrought from linguistic mechanisms falls short of its intended mark. There are certain subjective experiences in the human condition (i.e. powerful peak experiences) that cannot and will not be grasped by language alone and certain levels of conscious awareness (i.e. organisms interacting with their environment through echolocation or viewing the world with compound eyes) that will forever remain elusive. We can accurately describe in writing what it would be like to subsist as an inanimate object, stand embedded to the Earth Mother as a eucalyptus tree, or behave as a frilled iguana in the Simpson Desert of Australia however the superficial type of subjectivism afforded by written descriptions alone habitually falls short of capturing all those rich and multifaceted qualities of phenomenal experience standing outside the frontiers of human nature. Despite its sheer brilliance at facilitating empathic identification by connecting us with perspectives disparate and sometimes alien to ours, the faculty of imagination and its descended interpreter semantic language cannot bestow to us the gift of knowing exactly what it is like to be another–our factual knowledge about what is not part of oneself will forever remain proximal. This, in my mind, is the writing craft’s greatest limitation.