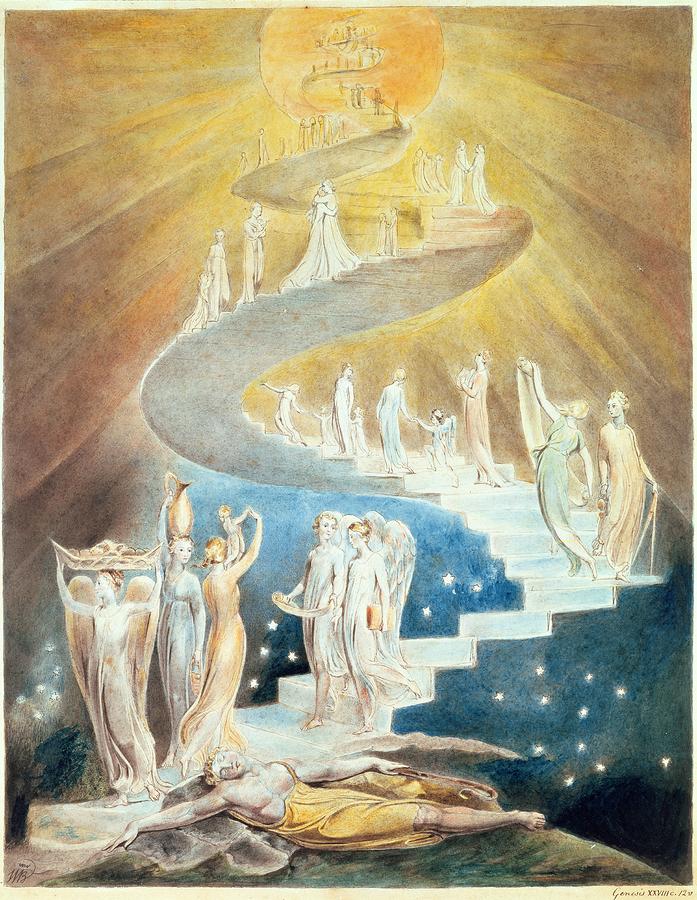

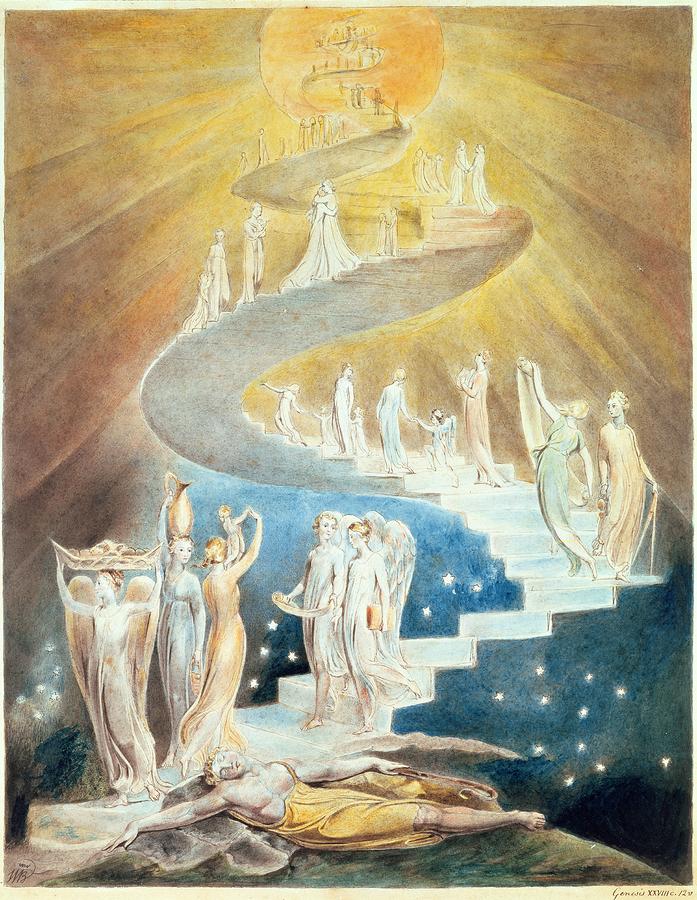

“A voice from heaven then said to me: “You shall see and hear”. So I departed into the spirit world and saw before me an opening, which I approached and examined: and behold!, there was a ladder, and by this I descended.” – The True Christian Religion, paragraph 332.

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1771) is perhaps the most important interpreter of the Western esoteric tradition in the eighteenth century, having pioneered a contemplative theological system of the cosmos that assimilated aspects of Enlightenment science, theosophy, and rationalism, and extended the empirical approach to the spiritual realm. To say that he wasn’t a spiritualist or spiritually-minded is akin to proposing that water isn’t wet or fire doesn’t burn. Interestingly the belief in disembodied entities had been entrenched in human consciousness for time immemorial and had formed a fundamental component of innumerable religious philosophies, though it isn’t until Swedenborg that the exact nature of the correspondence between the physical and the spiritual become clear. In adhering to a bird’s eye view of his life, one sees that the decisive vision of vocation in 1744 that enabled practical application of ethereal hierarchies, emanations, and correspondences, culminated with a spiritual dimension to Biblical exegesis, and formed a new Christianity were not unprecedented; in his formative years, the man had been exposed to Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism and the Christian Kabbalah by Eric Benzelius (1675-1743), his brother-in-law. Further, he maintained relations with Rabbi Haim Samuel Jacob Falk (1708-82), a Kabbalist and alchemist from London whose unrelenting esoteric exploits earned him national fame. Despite the mechanistic and scientific pursuits and activities that were preeminent and pivotal early in his intellectual life, Swedenborg’s formative environment was also underrun by occult philosophy and mystical lore.

The main exponent of Swedenborg’s spiritualism is, of course, the intuitive system of hidden knowledge that was emancipated when his religious persona finally broke through. The accompanying vision in which he was allowed to revel in the presence of Jesus Christ dressed in robes of “imperial purple and majestic white” was understood as a calling to fulfil a divinely-appointed role that involved experiencing the after-death transition into the transcendental, metaphysical realm first hand and henceforth enlightening the world of the living with specific details pertaining to the exact nature of that transition. Contrary to what many have written about him, Swedenborg was not a charlatan; if anything, he was a mentally-balanced, intellectual and single-minded individual who bequeathed to the notion of life-after-death a hitherto unprecedented sentiment of integrity and respectability. The scope of his paraphysical claims and talents is impressive: the communication of messages between the living and the departed, for which there is some viable evidence; visitations to ethereal dimensions like heaven and hell, the moon and the planets; conversing with angels, demons, and other disembodied entities therein; and even disengaging his own conscious from his physical body. All these controversial extrasensory endeavours, according to Swedenborg, were voluntary and could be induced at will utilising a controlled hypnagogic or semi trance-like state in which the individual conscious concurrently embodies an active and passive state of being. Ruminations in his personal dream diary, in which this contracted form of consciousness is called “passive potency”, definitely attest to such and recall the words of Rudolph Steiner: “Nay, there is another kind of vision which comes in a state between sleep and wakefulness. The man that supposes that he is fully awake, as it were, inasmuch as his senses are all active…” In any case this visionary faculty was to motivate a plethora of theologically and revelatory-flavoured pietistic writing, the most prominent being a compendium of eight books published in 1758 that were based entirely on Scripture, the Arcana Coelestia [Heavenly Secrets]. More importantly, though, it generated a breeding ground for the evolution of modern spiritualism and psychic research in the 1850s, as well as Transcendentalism and Mormonism, religious faction autochthonous to America that assimilated Hermetic, Gnostic, and magical conceptions about God and the greater cosmos.

As recent scholarship on the subject will confirm, religious philosophy was never quite absent from Swedenborg’s life. One’s biological parents are usually fundamental to their psychosocial development and spiritual orientation; Swedenborg’s father, Jesper Swedenborg (1673-1735), was a Lutheran bishop who acquired some very prominent positions within ecclesiastical hierarchy in Sweden. He was also well acquainted with the Puritan and Pietistic movements, and espoused paranormal beliefs. Emanuel confirmed the presence of these early influences in a written letter to Dr Gabriel Beyer of Goteborg, a Professor of Greek at Gothenburg University, in which he declared brusquely that, “From my fourth to my tenth year I was constantly engaged in thoughts upon God, salvation, and the spiritual diseases of men.” Soon afterwards, at the tender age of fifteen, Swedenborg went to live with Eric Benzelius (1675-1743), his brother-in-law, and that’s where the gilded gates leading to the labyrinthine terrain of esotericism were flung right open. The latter was an occult dabbler and enthusiast, having traversed Europe for the sake of gaining instruction in philosophy, descrying the Pythagorean Kabbalah, and engaging with like-minded people in esoteric circles such as the Philadelphia Society in London. When Swedenborg arrived, Benzelius was deeply ensconced in a Kabbalistic rendering of the New Testament under the auspices and guidance of a converted Jew named Moses ben Aaron of Cracow (1670–1716). This fascination with esoteric Judaism and “Orientalism” certainly rubbed off on the young, impressionable and intellectually curious Swedenborg, who would eventually imbue much of this knowledge into his own theological speculations. Swedenborg’s early fascination with mystical lore may have facilitated long-term intercourse with esoteric circles like the Jacobites, the Freemasons, and the Philadelphia Society in London with which his brother-in-law had sustained a close affiliation. In fact, there is some statistical likelihood to the notion that Swedenborg was somehow involved with the latter, given the aforementioned along with the cult’s propensity to identify powerfully with the Lutheran theosophy and Christian mysticism of Jacob Boehme (1575-1624). London was definitely an auspicious, momentous and providential hunting ground for Swedenborg, for it inaugurated lasting relations with Rabbi Samuel Jacob Folk (1708-82), a self-styled alchemist, practical Kabbalist, and magician whose reputed supernatural powers, miracle-working pursuits, and philosophical insights aligned Swedenborg with esoteric notions of vitalism, teleology, and salvific theology.

In 1710, Swedenborg disembarked in London with the sole intent of furthering the geometric and mechanistic frontiers of contemporary Newtonian science Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this phase of his life is the insurmountable fidelity towards all esoteric mentors. His occult-minded brother-in-law, Benzelius, had liaised with the great Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1673-1731) in 1697, an affair Swedenborg hoped to recapitulate when he eventually visited Hanover. Leibniz was away in Vienna at the time and was unable to host, though the geographical barrier did little to inhibit the subsequent influence. In fact, many of Swedenborg’s ideas derive from the intellectual musings of this great Cartesian interlocutor. Just like Leibniz, Swedenborg was convinced that the universe was hewn from a single substance that spontaneously divided itself into three different vibrational energies, forcing an anatomical split into three tiers, or layers: an intangible, spiritual and imaginative plane; an intermediary cerebral, moral and living plane; and a lower palpable physical plane. Everything that existed or had acquired an existence inhabited all planes in slightly variegated form, forming a quintessential law of esoteric correspondences. Existing at the echelon of the order, God, the Divine Mind and supernal spiritual sun, diffused through the multifaceted fabric in the manner that physical light travels through our solar system, passing through each of the spiritual, rational and natural spheres and instilling the triune counterpart of items and degrees with life. This theoretical framework encompassed Platonic repercussions, whereby the idealistic and utopian ideals so dear to man – unconditional love, compassion, wisdom, truth – might garner unhindered expression and potentiality in the highest heaven and in the being of God. Hence, under a Platonic tutelage the doctrine of Trinitarianism was rejected; Swedenborg was convinced that God had become wholly human in the figure of Jesus Christ and had somehow managed to preserve this persona after the crucifixion. God, therefore, was an everlasting mortal.

Swedenborg was a prolific writer. Many scientific works poured out of him during the first fifty-six years of his life, and a vast quantity of them explored and developed ideas well ahead of his time. These wonderful publications should have heralded the locus classicus of a Golden Age for Swedenborg; instead, they evolved into dissatisfying and intellectually frustrating experiences, explicitly because Sweden’s academic establishment ignored them completely. The perception of academic apathy and incessant lack of reassurance spurred an internal crisis that could only be reconciled through a resynthesis and redirection of intellectual thought. His scientific and mechanistic views were unable to harness a reaction, so he turned to his esoteric leanings for help. The first eruptions of the esoteric occurred eleven years before his decisive metaphysical vision, in a publication entitled, The Infinite and the Final Cause of Creation (1734), in which the purely mathematical and mechanistic notions of the world so dear to trial-and-error and chance were being usurped by an animistic and fundamentally interconnected one mediated by generative energies and teleological concerns.

Only six years later, two substantial publications called Dynamics of the Soul’s Domain (1740-1741) and The Soul’s Domain (1744-45) revealed hitherto unknown alchemical and mystical ambitions; to discover the base substance of which all things are made, as well as the seat of the human soul. To arrive at palpable conclusions Swedenborg borrowed the Neo-Platonic notion which viewed microcosm and the physical world as being a debased reflection of the Empyrean of God, the seat of Eternal Ideas and Platonic Forms. The soul itself, Swedenborg reasoned, was inexact by nature and for that reason belonged to a realm neither here nor there; to an intermediary dimension sourced by the archeus, a ubiquitous primal energy that was quite literally the life of macrocosm and microcosm, heaven and earth, God and human being. Neo-Platonic inclinations to view the cosmos as a multiverse or a hierarchical ladder of dimensions obfuscated Swedenborg’s assignment, at least until he could frame what the common denominator between worlds was and demarcate the soul. He proceeded along a radical path of inquiry that unearthed and weighed up disparately related forces – etheric fluid, magnetism, and electricity – in a bid to implicate this cosmic accomplice. The first two were dutifully rejected but found a home in Franz Anton Mesmer’s (1734-1815) philosophy of animal magnetism, otherwise known as Mesmerism. In the end, Swedenborg deduced that the medium responsible was an electrical vibration of sorts, a vital force, bringing to mind the idea of a coveted vital life principle that was propagated by the likes of Arnold of Villanova (1235-1312), Paracelsus (1493-1541), and Frater Albertus (1911-1984). According to Swedenborg this vital substance underpinned the cosmic spheres, both physical and paraphysical, as well as the soul of man with the individual differences and characteristics between the two being fomented by vibrational frequency or level of vibrations. The overarching substance was theorized to be indestructible, a singularity that implied immortality for the human soul when its operations were transposed to the physical level.

A critical examination of his biblical theology brings to light a multitude of other esoteric influences as well. Contemporary with Swedenborg was William Law (1686-1762), a prominent disciple of German mystic and theologian Jacob Boehme. Law’s theology stayed fiercely faithful to Boehme’s dualistic conception of God which entertained the controversial notion that objectified evil balances objectified good in His divine anatomy. Swedenborg distanced himself from the aforementioned Christian theosophers by stressing that he had never read any of their works, though striking parallels between their philosophical ruminations and his own definitely fuels speculation. Foremost was the idea of God as an inexhaustible and everlasting entity that formed from the intercourse of conflicting forces like water and fire, evil and good, male and female, inertia and activity, and so forth. His sapience, awareness, and ethereal being delimited the laws and precincts of the highest Empyrean, the spiritual world. Situated in a subordinate part of heaven was the angelic world, a realm in which the conjunction of intrapersonal forces within God’s eternal nature acquired a more tangible existence. Underneath the first two paraphysical tiers was a debased and flawed physical one fashioned by a cluster of fallen angels. The first two observed strict harmony and uniformity; the last, on the other hand, was a dissociative realm in which chaos, irreconcilable differences, and imbalance reigned supreme. Humans were in effect “fallen” angels, double beings comprised of spirit-souls that had become entrapped in the dross of physical bodies. The subsistence to all tiers of the cosmological totem pole was a blessing in disguise, for God could at once descend upon the earth in the personage of Jesus Christ to unclog the spiritual path and reinstate to all mortal denizens their divine inheritance. Remarkably, Boehme’s pensive fatalism didn’t extend to Law, who predicted that it was only a matter of time before a salvific phenomenon such as collective redemption finally unravelled. Swedenborg was able to attract Behmenists and practitioners of mystical theology like Thomas Hartley (1709-1784), Ezra Stiles (1727-1795), and John William Fletcher (1729-1785) precisely because he espoused analogous views.

Moreover, Swedenborg claimed that many of the unorthodox ideas pertaining to his doctrine of the divine Word were exhumed through visitations to the spirit world, a notion emphatically countered by contemporary scholarship which gravitates on the opinion that they were unconsciously sourced from esoteric philosophy. From his comprehensive knowledge of the Jewish and Christian Kabbalah, Swedenborg ascertained that Biblical exegesis contained a cryptic interpretation. Indeed, God had fashioned the divine message of Holy Scripture from a polygonal clay that made it intelligible to the hitherto untutored ears of man whilst at the same time awakening the intuitive and spiritually-inclined amongst them to those contours and ridges impregnated by much more profound and mystical denotations. This law of “accommodation” was neither unique nor original to Swedenborg, for it had typified the religious thought of the Christian Deists, as well as Moses ben-Maimon (1135-1204), a distinguished Jewish philosopher. Following along a path cleaved by the Kabbalists, he was also inclined to view letters, vowels, and consonants of individual words contained within Scripture as encompassing magical or supernatural powers. Swedenborg’s inimitable metaphysical process of revelation (i.e. spirit vision) bequeathed divine truths and techniques that enabled a correct interpretation of Biblical Scripture; the same totalitarian position was assumed by apocalyptic millenarians Joseph Mede (1586-1668) and John Hutchinson (1674-1737), as well as scholastic disciples of the latter like Duncan Forbes (1685-1747), John Parkhurst (1728-1797), and William Jones (1726-1800).

Hence even before the gates of the spiritual world were flung open by his all-defining visionary experience of 1745, Swedenborg was already cognizant of all esoteric particulars that would coalesce under a Christian aegis when he assumed a self-appointed role as hermetic messenger of the True Logos of God and interpreter of His Will. Of course, the creative integration of esoteric motifs into a New Christianity enabled Swedenborg to plausibly assume a role of mediumship through which the seventh and final exposé in the Book of Revelation might garner expression. The latter adhered to purely spiritual concerns, or as the apocalyptic Swedenborg would put it, to “the spiritual contents of Scripture”. The nature of these spiritual contents were explicated in Arcana Coelestia (1758), his colossal commentary on Genesis and Exodus, in addition to the more comprehensive The True Christian Religion (1771), both of which internalized the anticipated second incarnation of the Messiah and the Last Judgement foretold in the Book of Revelation. This interior process commenced in 1757 intending to reacquaint man with a spiritual realm bereft of collective consciousness through the true meaning of Biblical Scripture and restore balance between material and ethereal worlds. In transposing this holy truth from a presupposed literal to a higher ethereal level, Swedenborg was reiterating God’s suprapersonal nature; the material crucifixion of Jesus Christ never intended to atone for Adamic sin simply because the latter was a trivial matter unworthy of His attention. God was entirely transcendent and atonement was entirely unjustified. For all their brooding on theological matters, one has to wonder why this reasonable and coherent surmise never occurred to any other Christian philosopher or Founding Father.

Swedenborg’s spiritual crisis commenced when he was fifty-six. It was motivated by unaddressed unconscious elements, a psychic build-up of apprehension, suspicion, and confusion about the direction of his life that burst forth into consciousness as a series of strange and disturbing dreams. Their potency and eeriness was such that Swedenborg felt the need to transcribe them into a personal travel diary that became The Journal of Dreams (1743-1744). A brief glimpse of it reveals a cluster of dream imagery that is both variegated and intoxicating. In one, he becomes entangled in the spinning wheel of a machine that disengages from its parent body before spiralling out of control. In another, he witnesses a gardener purging bed bugs from a grove of plants right after having brooded over the purchase of a new bed. Women were often cast in protagonist roles as devourers and nurturers, illuminating what can only be unaddressed sexual repression or frustration; they were ominous demons equipped with teethed vaginas one minute and supernal guarding angels rigorously ascertaining the cause of his distress the next. Whatever the content or context, these were all musings of a vastly stressed, unbalanced, and dissatisfied unconscious. Often he would enter alternate states of consciousness for prolonged periods, vacillating between ordinary wakefulness and hypnotic trance, a passive viewer of this coming and going process until the culminating vision of April 7th 1744 in Wellclose Square in London unfolded where these visions suddenly acquired an unambiguous and perceptive character.

It begins with a violent tempest that ensnares Swedenborg and hurls him onto the ground like a ragged doll. He addresses a prayer to Jesus Christ, who henceforth materialises in all his majesty and inaugurates a cryptic conversation intended to motivate him. The following April Jesus appears again, this time through an intermediary consciousness between sleeping and waking known as a semi-hypnotic or hypnagogic state, to clarify the essentials of an apostolic mission vouchsafed to Swedenborg alone. With his paraphysical faculty of mediumship now opened, Swedenborg was free to explore the correspondence between the physical world and the worlds beyond at will, and hence cultivate a rudimentary theology. In theological and visionary treatises like The Divine Law and Wisdom, Heaven and Hell and The True Christian Religion, all published in 1958 and anonymously at first, he describes avid intercourse with spirits, both angels and devils, who shed light upon such circumstantial mysteries as the dual composition of human beings, eschatology and after-death states, and the anatomy of divine love. His main contention is that once a spirit-soul becomes ensnared in the physical world, the development of its psychological and moral habits are contingent upon the action of environmental forces. This evolution, substantial in the material world, does not cease upon physical corruption but pinches out any sensory input so that the now inwardly-turned and disembodied conscious can progress along a mental condition delineated by the repository of storied memories acquired during its corporeal lifetime. These modes of being do not determine whether one will ascend into heaven or descend into hell, for they are heaven and hell; hence, heaven and hell are states of mind that subsist after death. Here, Swedenborg’s inventiveness in creatively integrating occult or esoteric ideas into Christian theology is laid bare for all to see.

Indeed, his visionary theology brings to mind the contemporary axiom that “heaven and hell are where we make it.” In Swedenborg’s eyes, the perpetual dialogue between the physical brain and body, termed the outer or natural man, and the incorporeal mind, dubbed the inner or spiritual man, give birth to one’s character or personality. These bundles of biological and psychological impulses apprehended by habit are more or less inclined to an archetypal sentiment that governs all creation; that is to say love, the common good, or hate, the common evil. For the time that he remains alive, man is rooted to a realm of time and space in which his personality is moulded, shaped, bent, reformed and cast, according to information gathered by the sensory organs. When he finally passes into the realm of the dead, his disembodied mind, that being the inner or spiritual man, continues to exist in a timeless zone of thoughts and ideas, albeit in a state analogous to the prevailing sentiments of the outer man. By virtue of this fact, inclinations and tendencies in the world beyond are, to all intents and purposes, predetermined.

Swedenborg maintained that the ethereal dimension was divided into seven tiers, much like the individual rungs of a ladder: at the top was a tripartite subdivision of heaven into natural, angelic and celestial regions; the nethermost part was taken up by a tripartite subdivision of hell; and between the two lay a transitional realm harbouring the recently departed. The transitional world, dubbed psychonoetic by some seers and mystics, cleverly mimics the landscapes and contours of the physical plane so that a recently deceased might be fooled into thinking he’s still alive. Nevertheless, a gradual turning inward of personal consciousness sparked by the death of the outer man orientates the inner man to his spiritual north. Heeded by a likeminded spirit, either an angel or a demon, the inner man can ascend or descend the multidimensional ladder and network with societies of beings the exhibit the same psychic disposition. A placid and altruistic temperament, in conjunction with love for God, others and the collective interest are rewarded with spiritual freedom, or ascension into the heavenly spheres; alternatively, the narcissistic and those motivated by personal hedonism are subjected to abject servitude, sinking lower and lower into the Stygian darkness of the infernal regions. If every inhabitant of the netherworld was formally human, as Swedenborg would have us believe, then heaven and hell are states of mind that one identifies with during life and assumes permanently in the guise of angel and devil upon death.

No discussion of Swedenborg’s esoteric spirituality would be complete without a brief look at the visionary faculty through which all revelations pertaining to his contemplative theology were made. Swedenborg affirms he could consciously descry the external, physical plane and the internal, spiritual one simultaneously, entering and leaving the latter at will. Might there be any objective truth to such a claim? Swedenborg’s intellectual career and legacy are quick to offer up the first clues. Looking at his life from a holistic perspective, there is no evidence of a swift rise to fame followed by notoriety and decline that typifies, for instance, dubious mediums and magicians like Edward Kelley (1555-1597) and Aleister Crowley (1875-1947). Following his death, his philosophy transformed into a sect, the Swedenborgians, who influenced nineteenth-century esotericism in England and America. In addition, Swedenborg’s visionary descriptions of amphitheatres, parks, colleges, palaces, and other places are remarkably detailed and descriptive, preternaturally so. They’re a world away from the parabolic displays that typify the written discourse of pathological liars. These terms jettison the notion that he may have been a charlatan.

Save for a genuine power of mediumship, the only feasible explanation is a Jungian one; Swedenborg’s hypnogogic visions of spirits, angels and demons, were in effect controllable daydreams that explored the archetypal or racial psyche. The exact same method, identified as “active imagination” by Carl Jung (1875-1961) in the early twentieth century, was utilized by the latter as a curative tool in the practice of psychotherapy. These inner, unconscious processes of primordial life energy sweep in and out of our personal conscious like the oceanic tides, spewing forth ostensibly disparate thoughts, ideas, and images that materialize and dematerialize entirely of their own volition. We’re not in control; if anything, we’re spiralling out of control. In this state of being the processes of creation are intuitively felt as coming from without; they are ruminations of a divine pantocrator and we passive observers caught in its spell. Swedenborg, who initially published his theological works anonymously, no doubt harboured the same belief. He refused to declare authorship on grounds that he was merely a vessel for original cogitations of a higher formative force, that being God, to secure expression in the physical world.

For Swedenborg, the result of dabbling in these alternate states of consciousness garnered results so extraordinary that people began to look at life after death and the occult with a newfound dignity. The evidence validating the renowned incidents is circumstantial, and while liaising with the spirits of the dead might fail to suspend disbelief for the sceptical majority one must at least entertain the possibility that he acquired the requisite information “paranormally”. In 1761, Swedenborg helped the widow of the Dutch ambassador vindicate a payment already made to a fraudulent silversmith for a tea service by contacting her deceased husband in the heavenly realm who proceeded to pinpoint the exact whereabouts of the receipt. Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia (1720-1782) also got more than she bargained for when Swedenborg assumed mediumship for her dead brother, the Prince Royal of Prussia, and responded to a personal letter of hers that had remained unanswered. On the evening of 19th July 1759, Swedenborg related lamentable news to fellow guests at a party in Gothenburg that a conflagration had just ignited in Stockholm, and only a few hours later, that it had been snuffed out three doors from his own residence. Three days afterward an envoy arriving from Stockholm confirmed these prognostications. The last was a most fitting end for a man of his spiritual standing; like a great many mystics and seers, he correctly foretold the date of his own death.

Swedenborg’s legacy is an interesting one. Only four years after his death, a director of a Manchester parish by the name of John Clawes (1734-1831) began introducing Swedenborgian theology into the religious worldview heeded by the Anglican Church. His major efforts in accurately translating works into English from their original Latin did not go unnoticed for very long. Comprised of contemplative material of an esoteric nature it caught the collective eye of many groups, particularly Freemasonic groups like the French Prophets. This growing vortex of interest surrounding the great man and his visionary books spurred denominational institutionalization in 1783, when it prudently stepped into the world as the “Theosophical Society”, the first incarnation of the Swedenborgian “New Church”. Everything was meticulously thought out; even the choice of name was purposefully designed to entice its principle market, the Freemasons, who thrived under the aegis of esoteric study. An increased emphasis on an experimental approach to the spiritual world was paramount to a group which was trying to differentiate from the secular rationalism induced by the Enlightenment thinkers, and in 1785 it assumed its second incarnation as the “Society for Promoting the Heavenly Doctrines of the New Church designed by the New Jerusalem in the Revelation of St John” to reflect this vital alignment. Its third and final incarnation came in 1787, when it dropped the longwinded title for a simpler one in the “New Church”. The primary concern for Samuel Noble (1779-1853) who led the Swedenborgians under this new institutionalised banner, was to facilitate accurate translations of texts for group readings and discussions. His professional was detrimental to the sect, for it precluded social and congregational interaction that serve as adhesive by creating bonds and kinship between members and thus ensuring longevity.

Nonetheless, Swedenborg’s contributions to the history of Western esotericism and Christian mysticism were comprehensive and enduring. The development of modern spiritualism and research into psychic phenomena, both of which arose in the 1850s, would not have been the same had Swedenborg’s visionary material remained in the dark. While the notion of Mesmerism popularised by Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) was a chief conduit, its philosophical underlay was indebted to Swedenborg. Mesmer’s inclination to view animal magnetism as the prima materia pervading the corporeal and ethereal worlds and acting as a common denominator between the two had been theorized by Swedenborg many decades before. In the Mesmeric cosmology, spirit contact and psi phenomena are possible when one enters a psychic state both active and passive in which the unconscious will is allowed to act on the all-encompassing vital force connecting the subject with the greater cosmos. Mesmer calls it magnetic somnambulism, but anyone familiar with the history of esoteric ideas will immediately recognise its former identity as the hypnagogic states or waking dreams Swedenborg used to transcribe information from the spirit world; the two are one and the same concept. In any case, descriptions of the other world in pietistic literature of the late nineteenth century such as Spirit Teachings (1883) by the British spiritualist Stainton Moses (1839-1892) match those descried in Swedenborg’s visions. Outgrowths of Swedenbogian philosophy also occurred on American soil: Transcendentalism, with its Neo-platonic overemphasis on ascension of the spirit-soul through the dimensions; as well as Mormonism, a syncretic religion comprised of Gnostic, Hermetic, and magical ideas allegedly birthed through angel-human interaction.

In so far as his role in modern spiritualism is concerned, Emanuel Swedenborg assumed the role of catalyst in offering a practicable and transformative conjunction between the inner divine and the outer natural worlds in much the same was that the human brain arbitrates between electrochemical impulses and intelligible thought. Early interests and activities exposed him to Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and fashionable Christian Kabbala, denominations of inquiry that provided much of the fertile esoteric humus on which a contemplative theology based exclusively on mystical revelation would eventually take root and flourish. In April of 1744 and 1745, unambiguous visions of Jesus Christ inaugurated the opening of his spiritual sight and divinely confirmed his mission to “explain to men the spiritual meaning of Scripture”. Without doubt, this newfound self-appointed role as messenger and interpreter of the Divine Word of God served as the impetus behind full-fledged intercourse with spirits that pervaded an ethereal hierarchy. In his plethora of theological works, he described in immense detail the anatomy of a transitory after-death realm neither here nor there, where the soul awakened to a spiritual experience or state of mind conditioned by moral choices made during the course of its corporeal life. Further, his dream journal vindicates hypnagogic states of consciousness as the medium through which voluntary entry into the spirit world was made. This scientific and experimental approach to subject by its nature allusive, unspecific and transcendental was unique, an original contribution to esotericism that would birth a Swedenborgian sect known as the “New Church”, offer its theoretical underpinnings to institutionalised denominations in America like Transcendentalism and Mormonism, and spur the nineteenth-century development of modern spiritualism and psychic research.

As for the authenticity of his powers of mediumship and all claims harnessed under a religious persona, one can only wonder. Perhaps the validity of exercise shouldn’t be contingent on what we believe, but on what Swedenborg himself believed about his visionary experiences and writings. When challenged on this he flatly replied, “I have written nothing but the truth, and could have said more, had it been permitted.”