The worldview of our ancestors is as variegated as it is deep. One particular method of healing that touches upon ancient medicine though are much broader in its epistemological scope is magic. Magic is, amongst other things, an attempt to thwart, divert, accelerate, or fiddle with the natural order and fundamental harmony or the inner workings of fate. Contemporary mechanistic science views magic as a primitive and altogether unsuccessful pseudo-attempt to gain mastery over nature through techniques that include what many have labelled black or white magic. If the intent is purely malefic, then the practitioner makes use of the former; if, on the other hand, the intention is beneficent then the practitioner works with the latter. According to most ancient cosmologies, a conjuration of black magic aims to generate disease and subsequently squeeze the life out of the victim to which it is directed whilst white magic aims to cure it.

Modern sociology and psychology tend to see ancient magical practices as archetypal projections of traditional and ethnic attitudes onto the formless hyle that is the material realm. The ignorance of physical, impersonal laws that bind the cosmos does not confound magical theory simply because magic and countermagic transpose them to a level in which the forces of Mother Nature are perceived as personified powers eternally at war with one another. If the forces in question could be bent or appeased through personal incantations and conjurations, rites or ceremonies, then the magician or practitioner of healing could facilitate positive outcomes in the heterogeneous areas of human life that the natural forces directly affected like the fecundity of the earth and her many beasts, meteorology, and the sphere of personal health.

From textual and anecdotal evidence we can tabulate about five different tributaries of magic: the practical application of drugs or poisons through cavities in the head, usually the mouth and nose; paraphysical phenomena induced by the powers of a practitioner’s mind that manifest as clairvoyance, telepathy, or psychokinesis; hypnosis or trance states prompted with the help of repetitive audio and visual cues; jugglery or fraudulent visual tricks or illusions that may be passed off as genuine feats of magic; and suggestion or autosuggestion. The last of these happens to be the most effective and efficacious, simply because a thought form that has possessed the mind of an individual or an entire group of people begins to acquire a tangible existence on the objective plane. Everybody knows the power of the placebo effect in experimental methods utilized by behavioural and cognitive psychology, and this sentiment can be extended to include all communities that have developed religion, magic, or some form of esoteric spirituality for social cohesion.

One would not be wrong in saying that the belief in magic is quite like a resistant weed, having persisted through all times and places under the aegis of sorcery, natural magic, witchcraft, voodoo, and many other designations that fall outside the frontiers of modern science. As a link between the divine and material universe, magic and countermagic are the closest things to an omnipotent power in the cosmologies of autochthonous cultures that renders the miracle of nature, the creation and destruction of human life itself, rudely and unjustly accessible to mere mortals. Amongst the indigenous peoples of South America, Australia, and Melanesia, magic is not a superstition; it is an objectified reality that is as solid and tangible as the animals they hunt for food and the freshwater lake where daily rations of water might be collected.

Certain indigenous tribes of central Australia adhere to the belief that somebody can be murdered with a “pointing stick” or “pointing bone”. In such a case the afflicted or the one being “boned” by the adversity usually goes into an epileptic-like fit, foaming at the mouth whilst attempting to scream at the top of his or her lungs. The victim’s emasculation at the hands of the curse is gruesome; he or she may experience involuntary muscle spasms, twitches, mortification, and profound fear. Within a matter of hours these physical and psychological symptoms morph into a complete withdrawal from psychic and communal life in general, and if the Nangarri or medicine man does not intercede to treat the individual through coutermagic the latter’s fate is to die a painful and torturous death. A Nangarri agreeing to treat the afflicted will initiate a magical ritual whereby the “evil” is localized, extracted through the proverbial mouth-sucking procedure and waved about a small audience, usually the sufferer’s relatives, as evidence of counteraction.

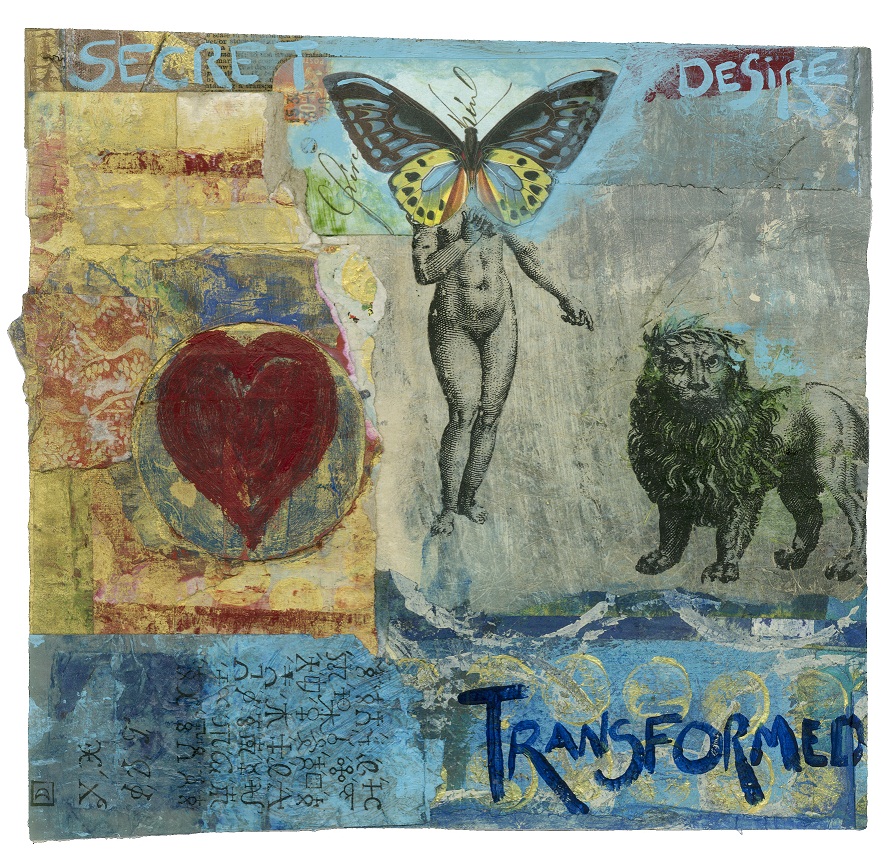

From what we can see, the magician lived in a fantastical world of feasibilities. He or she could act in the manner of a deity to psychogenically destroy the soul of his intended victims and spontaneously regenerate them; afflict disease or ailment in the physical body and spontaneously remove them; and alter the trajectory of autosuggestion or suggestion in the minds of those persons that were convinced that they were victims of black magic or voodoo so that the debilitating effects of the condition, imagined or otherwise, ceased to be. In such cases the magician or healer was burdened with an additional task of localizing the origin of the disease or its mastermind.

In hindsight, magic operates through causality or the cosmic law of cause and effect. An act of black magic initiates a cause malevolent in nature and intent towards a particular individual and an act of white magic or countermagic aims to negate the cause by murdering its conscious originator or prevent it entirely through the ample utilization of apotropaic amulets called talismans. Many of these beliefs and practices subsist in the rustic populations of developed countries like Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Malta, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom.