Santorini was once a quiescent island composed chiefly of limestone and schists. It became the Aegean’s protagonist of periodic cataclysm only after the present Hellenic Volcanic Arc came into existence some three million years ago, a time when eruptions began at a depth of one thousand meters on the adjacent Aegean seafloor. Since then, the volcano has reconstituted and dismembered itself eleven times. The last of these paroxysms occurred in 1520 bce, a period in which at least two Minoan settlements were thriving on the island. It unraveled as four main phases of activity around a shallow flooded caldera, lasting about four days and releasing the collective energy of thirty hydrogen bombs.

The volcano came to life with sulphurous emissions of steam, gas and smoke from the volcanic cones beyond the South Bay. Subsequently, a fluid ejection of popcorn-like pumice and basalt fragments from the central vent blanketed the island with powder white blankets resembling snow. After a momentary pause to clear its throat, it proceeded to spew an undulating cloud of superheated ash several kilometers into the sky. The ensuring darkness hovered above the stratovolcano like a malignant tumor and soon larger pieces of fine white pumice pelted back down on the beleaguered island, shrouding it in layer upon layer of volcanic debris. Little by little, the caldera grew until seawater entered from the South Bay, creating phreatic explosions, ground water mixing with ascending magma that sent lava hurtling in all directions. The incessant convulsion wracked the wide, funnel-shaped vent with such force that remnants of shield volcanoes that had accumulated within the pre-Minoan caldera crumbled completely, their remains shooting out in horizontal blasts that fleetingly dammed back the sea.

All in all, the volcano spewed its guts out with such urgent turbulence that thirty cubic meters of magma were expelled into the atmosphere. The rapidly emptying magma chamber below Thera formed a gaping chasm hundreds of meters deep which could no longer support the weight of the island’s heart center. In one ear-splitting roar, the walls of the disintegrating crater collapsed vertically into the abyss. Torrents of water rushed in to fill the gaping fissure, generating further phreatic explosions and shallow-seated earthquakes that exceeded ten on the Richter scale. These subterranean earthquakes would have vibrated the seabed around Thera as the caldera collapsed in on itself, spawning three hundred and sixty degree tsunamis that would have assaulted every island in the Aegean Sea. For years afterward, the sunsets would have been a deep, blood red.

The Therans of the day would have interpreted the rumbling and the emissions of gas, steam and smoke from the volcanic cones as the divine displeasure of the Great Mother Goddess and her entourage of lesser deities. Just as with their Minoan cousins they would have made sacrifices to placate their gods’ wrath, although as the premonitory tremors increased in frequency and severity their trepidation would have no doubt have gotten the better of them. Those not overcome by primitive terror risked staying and forfeiting their lives in due course. Everyone else gathered one’s personal belongings and took to the seas in search of a new home.

What became of them remains a mystery to this very day. Might archaeological finds in the near future shed light upon their destiny? Perhaps they colonized some remote corner of the Aegean and continued their enormously complex matriarchal civilization elsewhere. Sadly, there is no evidence to support such a comforting and satisfying conjecture. More likely, the Therans disembarked on an Aegean island in close proximity to the major geological convulsion. From there they would have watched the natural disaster unfold in complete awe and reverence. They’d have splayed themselves out along the shore in silence, churning through the possibilities of what might have angered their gods―until the tsunamis arrived to assail them. Ironically it was their deserted homes that survived to tell their tale, quiescent under layers of pea-sized pellets of pumice that preserved them until the forces of erosion brought this forgotten Bronze-Age world back from the dreaded depths of Tartarus.

It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos (1901-74 ce) honed in on the Aegean folk memory of the disaster. Marinatos had formulated a clandestine theory that Minoan Crete and Plato’s Atlantis were one and the same, though what actually convinced him to begin excavations was a pivotal supposition put forth by seismologist Angelos Galanopoulos who redefined Plato’s story as the commemorative fate of two islands– Crete and Thera. In this plausible reconstruction, he proposed that the first and larger of the two islands (Crete) may have been the royal state whilst the smaller one (Thera) was probably the metropolis or Capitol city and religious center. Late in the same century, archaeological excavations revealed the opposite; Knossos on Crete had been the Capitol of the Minoan empire and Thera merely one of its many outposts. Nevertheless, Galanopoulos’ confounded hypothesis held no sway over the desired result.

Convinced that the Theran volcano had contributed greatly, if not wholly, to the demise of Minoan power on Crete, Marinatos began digging in 1967 ce, with excavations focused near Akrotiri in southern Thera. At first he stumbled across stone tools, pottery, mortars and pestles, but as he penetrated deeper into the layers of pumice, the remnants of man-made walls, cobbled streets and cooking utensils came to light. The discovery would go on to shake the very foundation stone of archaeology itself, revealing a Bronze Age town with a structured assembly of roads and houses underpinned by a subterranean network of elaborate land drainage ditches, conduits, and navigational channels. These were linked to cesspits, and took the waste water and sewerage from the indoor baths and lavatories of homes by way of clay pipes cemented within their walls. The archaeologists working under Marinatos revealed that the indoor lavatories worked in a comparable manner to the ones in use today. The waste falling through clap pipes to a chamber below would be flushed into a cesspit by water from the town drain, with the pipes interconnecting in such a way that a siphon effect was formed, drawing repulsive odors down the pipes and into the lavatory.

In the end, what Marinatos thought would be a systematic excavation of a few primitive cobblestone structures turned out to be the rediscovery of a Bronze Age civilization whose people had attained a level of sophistication and advancement equaling that of Minoan Crete. In actual fact, the architectural features unearthed at the archaeological site of Akrotiri mimic those that seen amidst the Minoan ruins of Knossos: masons’ marks, light wells, peer-and-door partitions, pillared crypts, ashlar facades, wooden columns on stone bases, adyta and the erection of multi-story buildings. Strangely, the destruction of Thera and the subsequent collapse of Minoan civilization were marked by the disappearance of these technologies from the face the earth. From this time forth, evidence of their existence could only be found in Cycladic traditions which passed orally from generation to generation. Successive retellings of oral folklore have the detrimental effect of confounding the story’s elements to such a degree that the kernel and essence are eventually lost. This would have certainly been the fate of the Minoan super civilization and thalassokratia had it not been for Plato, the preeminent philosopher of the classical world who was so impressed by the rise, the gargantuan feats, and the tragic downfall of this phenomenal culture that he immortalized in his legend of Atlantis.

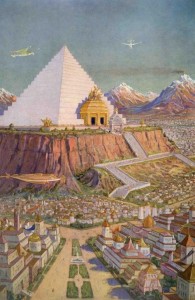

In Plato’s account, Atlantis was a rich and bountiful island continent in the Atlantic Ocean, with a stunning Capitol of the same name situated at the extreme southern tip of the island. It appears that the land mass was oblong in shape, with broad, flat and low-lying plains in the interior that were well fortified by towering mountains that dotted its coastline against the destructive forces of wind and sea. The land, contoured much higher and precipitous to the north, leveled out toward the south in a way that evoked the contrasting landscapes of Greece proper, with a surface area of about 203,500 square kilometers. Most of the southern face in which the vast, fertile plain lay was crisscrossed by subsidiary ditches whose perfect grid pattern epitomized Plato’s love of geometrical form. The canals interlinked and formed major highways through which sea vessels transported metals, precious stones, timber, and a copper-gold alloy, orichalcum, across the island.

Lying at the south end of the continent, the city of Atlantis was a bustling metropolis whose design could only have been inspired by a lover of engineering, architecture, and mathematics; one who perceived numbers and fractions as the divine signature of a universal progenitor. It was comprised of three concentric ringlets of land, each separated by a transport and irrigation channel. Legend tells that the canals had been hewn out by the sea god to guard his mortal wife, Cleito. Centuries afterward, the city’s inhabitants conjoined these rings of land with bridges. The outermost of these, half a kilometer wide, joined the inner metropolitan center to the greater city beyond. For residents of the metropolitan region, admission to the sea was via a wide canal which branched off from the nether point of the third concentric island and sluiced through the greater metropolis. Both the inner and outer metropolis, fortified by a thick stone wall, covered a total area of about four hundred square kilometers.

If one were a tourist visiting Atlantis, he’d ply the great canal that linked the sea with the mighty metropolis in a ship and dock at a great harbor. Disembarking, he’d walk overland across the first of the bridges and enter the outermost and largest of the concentric islets. At once, it would occur to him that the Atlanteans were master masons, having constructed parklands, lavish gardens, and civil buildings like stadia and gymnasia that wrapped around the entire length of land and blended into one another in an aesthetically pleasing manner. More than likely, he’d be impressed by the tri-color theme exhibited by the buildings of the Capitol, a phenomenon wrought by blocks of stone quarried from local mines that were black, white or red. The tourist would then traverse a second bridge to a smaller ring of land on which residential houses and equitation centers were built. Here it might occur to him or her that the enormous stone walls surrounding each concentric ring of land are sheathed in a different metal; the outermost brass, the middle tin, and the innermost orichalcum. The more observant might also realize that the walls themselves are decked by towers and gates at points where bridges and tunnels pass through them.

By crossing the final bridge, the tourist would enter the dreamy realm of Atlantis’ magical metropolitan heart-center. The structure of Atlantis mimicked that of ancient Athens, built around a well-fortified acropolis which enclosed a cluster of palaces, gardens, temples and baths. According to legend, Poseidon, besotted by the island’s natural beauty, snatched it as his own fiefdom. He proceeded to carve out three concentric rings of land at the south end of his island, jabbing his trident onto the ground of the innermost one so that two natural springs spurted forth. The two jets, one of hot and one of cold running water, supplied nourishment to the five pairs of male twins he sired with his mortal wife, Cleito.

In later times, the Atlanteans commemorated this divine feat by erecting a megalithic temple to this sovereign of the sea. Standing at the highest point of the fortified hill, the tourist would lift his gaze up to a forest of silver-coated pillars; these bear the laborious weight of a temple ceiling comprised chiefly of ivory, silver, and orichalchum and embellished by mythical figures made of ivory inlaid with gold. Astonishingly, the entire structure is shrouded by silver save for the gilded pinnacles. Inside, the centerpiece of the temple reveals itself as a golden statue of Poseidon at the helm of a chariot drawn by six winged horses. Holding his trident in one hand and the chariot’s reigns in the other, he stands ready to command the winds, gales and breezes which morph the ethereal face of the sea. The statues of a hundred sea nymphs riding on dolphins encircle him in a manner reinforcing his incontestable power over the water element. For a tourist, the spectacle of lesser sea deities saluting Poseidon might serve as a blatant reminder to always seek his blessings before attempting to traverse the pelagic waters.

Drowned World

In 2005, the United States suffered its costliest natural disaster when Hurricane Katrina ripped through the south-eastern corner of the country. It instigated damages to personal properties that amounted to $81 billion US dollars and claimed over 1,800 lives. Much of this devastation came after the levee system in New Orleans, Louisiana failed, sparking episodes of flash flooding that saw much of the metropolis submerged in water for weeks on end. Today, I will conclude with a poem entitled Drowned World which appears in Sensations Magazine, 21st Century America Issue 48, Fall/Winter 2010, and explores a fleeting memory of the event.

It’s cold, humid, wet

and calculatingly evil

inside this room

as if Katrina

had struck

only moments ago.

Words rolling onto

the page like

frothy tsunamis

full of anger

originate from

ruptures in

the earth below.

Tectonically challenged

and volcano’ed out

the outpouring

of grief streams

like hot lava

through heart and veins.

Reprieved by

the frothing of memories

on its watery surface,

then nails find flesh

but won’t loosen

the afterlife’s reigns.