Everybody is a product of their environment and Sigmund Freud was no exception. His formative years would have entailed an intimate acquaintance with the same intellectual treasure chest that helped shape his schematic repression model. Nested within were scientific positivism and Darwin’s theory of natural selection, reductionist philosophies attempting to sweep aside the paraphysical outgrowths of psychiatric Romanticism and forge a sharp barrier between the ‘pseudoscientific’ and the genuinely ‘scientific’. Acting in the interests of empiricism, positivism promptly decreed religious ideology dangerous and metaphysics superfluous. Freud found authoritative allies in both. He also inherited without reservation conventional, mid-nineteenth-century opinions about the nature of the unconscious. Prompted to the clinical frontline by Mesmer and Puységur, this undulating, pelagic body had since manifested unusual phenomena across the entire human population illuminating the qualities of ubiquity and universal law. Mercurial nature aside, it encompassed an uncanny ability to surface full-formed mental contents in the same manner that the cerulean ocean expunges a gamut of scallop shells, seaweed, and bits of coral from its nebulous centre.

These days there is a constructivist slant to the phenomenology of perception, meaning that both nonverbal and verbal-reflective enunciations manifesting as integrated streams of consciousness are implicitly understood as creative potentialities without a presentience or preexistence of their own. We see ourselves as neurobiological world-simulators betrothed with repeated mental acts of creation on both the personal and collective level. However in Freud’s day the perceptive mechanism underlying consciousness wasn’t seen as a phenomenon; it was an epiphenomenon, a passive outcome of chance events. The content able to manifest wasn’t a contrivance of the present but was supposed to remain latent in the somnolent depths of nonexistence until an exterior or interior event forced the chthonic gates of the unconscious to open. Once it had surfaced, it was re-membered as an aspect of integrated consciousness. For many a psychiatrist, magnetizer, or philosopher, the uncertainty of not knowing what would blast through to the surface was disquieting, and the inability to distinguish the real from the imagined in this ethereal landscape was equally exasperating. The appropriate diagnostic tools had not yet been developed, let alone theorized. Freud built his repression theories around these empirical assumptions.

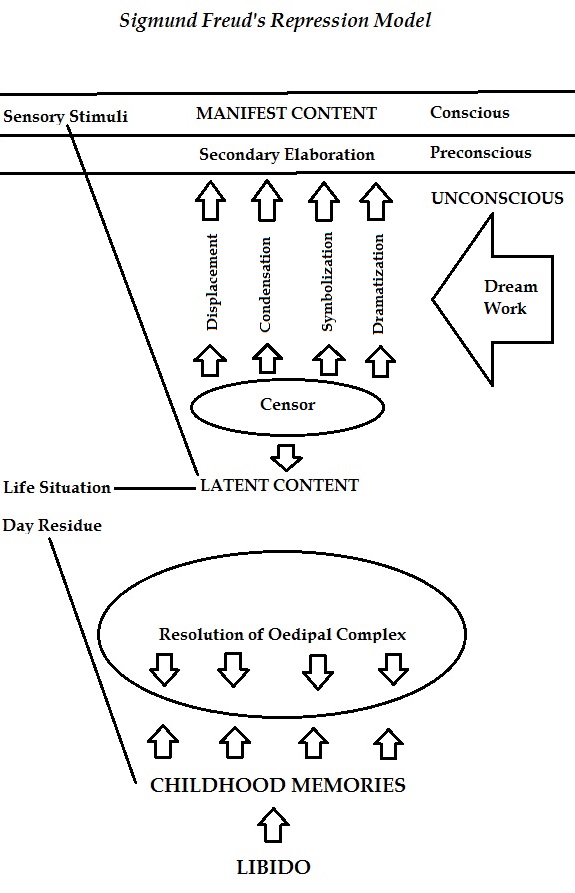

Turning our attention now to Freud’s repression model, it becomes apparent that human consciousness has become a sedimentary remnant that takes shape once instinctual drives and defenses have finished roughing up the landscape. We must penetrate through this superficial uppermost layer encompassing a detailed record of contemporary psychic life–idiosyncratic notions, neuroses, and psychoses–if we are to understand the processes of sedimentation mediating the whole psyche. Freud assures us that beneath this dark veil of appearances are a succession of horizontal psychic strata, the preconscious and the unconscious, in which actualized mental contents await sensory expression. Lowest is a subterranean reserve that perpetually feeds a Hadean chamber crammed full of unobstructed sexual wishes and fantasies with inexhaustible sexual energy or libido. Just as the deepest layers of geological strata contain fossilized remains of plants and animals now extinct, so too does the unconscious contain a chronological repertoire of painful childhood memories. Similarly, the psychological ontology mirrors the geological constituent in that the subterranean chambers can generate enormous pressures whose naked thrust can twist, fold, invert, or even decimate the uppermost integrated echelon of consciousness.

Telepathic knowledge of these ego-building processes are stored within the psyche; knowing full well that complete circumvention of such catastrophic phenomena is impossible, it resorts to a secondary interjection aimed at minimizing trauma by creating a dimensional displacement in the intermediary strata so that what reaches the conscious surface from the antithetical unconscious is merely a distorted version of the earth-shattering pathogenic content, a slight tremor instead of a full-blown earthquake. Displacement is not only an unconscious defense mechanism that keeps latent mental content at bay, but an enforced somnolence and a self-sabotage preventing the ego-conscious from being overrun by madness and from encountering an inconvenient truth. Psychic paroxysms that cannot be blunted by such a displacement break through to the surface, manifesting as night terrors during sleep and neurotic symptoms during wakefulness. Consequently maintaining a robust lifestyle free of mental and physical illness is contingent upon the aptitude of one’s defense mechanisms, or so we’re led to believe.

In Freud’s cosmology the intrapsychic cable bridging the conscious with the unconscious; the present with the past; the neurotic behaviors and parapraxes with the pathogenic memories and fantasies; the manifest content with the latent content; and the literal with the symbolic is the personal dreamscape. As apparatuses of the unconscious, a dream will exploit pictorial images to personify a conglomeration of thoughts, drives, and desires ensouled by the sexual forces of the libido. Any therapeutic venture, clinical or otherwise, that can expose the true meaning of the latent content and release it back into the conscious field of presentation will also effectively obliterate the negative and positive pathological symptoms to which the unmasked mental content is correlated. Hence the positive identification and clarification of pathogenic content via dream work and the catharsis of a defense neurosis are construed as alternate sides of the same coin. Dreams acquired a far more prominent position in the psychology of the unconscious under Freud, an argument that was elaborated at length during the aftermath of his creative illness and found voice in both The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and The Psychology of Everyday Life (1904).

Accompanying the rise and evolutionary development of Freudian dream analysis was a conceptual drift from traumatic origins to instinctual drives and libido; from hypnoid to defense hysteria; and from lackadaisical faith in hypnosis as an inductive psychotherapeutic technique to religious faith in free association as the sole manner of entry into the unconscious. The Janetian conceptualization of dissociation could not be reconciled with phenomenological vicissitudes whereby intrapsychic conflicts and instinctual drives were credited with aetiological prominence in hysteria and neurotic ailments, and so Freud was left with no other feasible option but to lump it together with repression under the heading of an ‘active defense’. This categorical modification is most palatable in the International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (2005), an encyclopedic work of astounding proportions from which prepsychoanalytic dissociation with its multiple personality and multiple nuclei of consciousness are markedly absent. Their sole mention comes in the articles for ‘Hypnoid States’, ‘Hysteria,’ and ‘Conversion’ where they are credited to Josef Breuer, and there only in the most superficial sense–as obsolete eccentricities that were theoretically rectified by Freud.