Asclepius, the Greek god of healing and medicine, was a son of the god Apollo and Coronis, a Thessalian princess, and was highly revered in all of Greece proper. His name denotes the condition of cutting something open and he is best known for his wand called the Rod of Asclepius. The latter is comprised of a staff surmounted by an entwined serpent and occasionally a pair of wings, mythical symbols which recall elements indigenous to the divine like knowledge, wisdom, grace, faith, magical power, authority, the duality of being, and fundamental unity. Unlike so many other symbols, the Rod of Asclepius s is fittingly associated with this archetype of the first physician. Asclepius is an Olympian deity who busies himself with the reinstatement of vitality to the dissipating life force of an ailing mortal patient; hence it makes perfect sense that he should be armed with the appropriate antidote (serpent) as well as an obligatory intellectual capacity for intuition (the wand and the wings) that facilitates pertinent and ethical use of it.

The ancient myth relating details of the events leading up to his birth are both fascinating and melodramatic. According to legend, there was once a son of war-loving Ares named Phlegyas who ruled the Lapiths, an Aeolian tribe from the region of Thessaly in Greece. Phlegyas enjoyed fortuitous relations with many concubines, one of which culminated with the birth of a beautiful daughter, Coronis. This girl’s physiognomy and charm were mystifying and magnetic; any male, god or mortal, who laid eyes upon her fairest beauty fell head over heels in love. In due course an already betrothed Coronis was unlucky enough to be sighted by Pythian Apollo, whose instant reaction was to woo her. She capitulated to his will but made the tragic mistake of keeping details of the encounter to herself for fear of rejection and ridicule. She didn’t have the courage to admit her wrongdoing to Ischys, the Arcadian prince who would soon become her husband, nor front her divine lover with this premeditated royal arrangement.

The latter was to prove fatal. When Coronis’s day of matrimony finally came, a white crow standing sentry over the royal palace overheard details of the intended proceedings and flew straight to Delphi with the intention of breaking the news to Apollo. Needless to say the consequences weren’t very becoming. Apollo was so infuriated by Coronis’s deception that he cursed the poor crow before it could finish its grim soliloquy, turning it a jet black. Then he ambushed the royal couple with the help of his sister Artemis; the brunt of his fury was dutifully imprinted onto the tips of arrows that pierced the heart of Ischys, whilst Artemis’s impaled Coronis. Interestingly the young Coronis happened to be pregnant at the time of her death, a hitherto unknown fact to Apollo who steadfast took the appropriate measures to ensure survival of the unborn infant. He liberated the baby boy from the womb of its dead mother by preternatural means and bequeathed it the name Asclepius before entrusting its care and wellbeing to Chiron, a benevolent centaur who raised orphaned children in amorous environments and offered instruction in the divine art of medicine. Asclepius possessed a natural flair for detecting illnesses latent in the human body and ascribing the appropriate remedial therapies, a talent which propelled him to the frontier of fame in Greece proper. Sadly the same talent proved to be a hidden curse, for when Asclepius transcended the corporeal limitations imposed on mortals by reinvigorating Hippolytus from the dead he exasperated Zeus like never before. Acting partly out of enmity and partly out of jealousy, the mighty Olympian conjured a violent tempest and directed it at the ill-fated Asclepius who was struck down by one of its many thunderbolts.

Many classical myths attribute Asclepius’s ability to reanimate the dead to the acquisition of Medusa’s blood through the intercession of Pallas Athena, who managed to collect it in phials when Perseus was beheading the dreaded gorgon. Word has it that the blood of gorgons exhibited a dual metaphysical nature; when collected from the right side it would act as a potent elixir to ensoul a lifeless carcass but when drawn from the left it reverted to a deadly poison able to dissolve living tissue. Asclepius appears to have begun his illustrious career in Greece proper as a mortal hero, a contemporary physician par excellence whose immense popularity earned him an illustrious position amongst the Olympians during the Late Classical Period. He married a woman called Epione of which little is known and had six daughters: Hygeia (Hygiene), Iaso (Medicine), Meditrina (Serpent Bearer), Aceso (Healing), Aglaea (Healthy Glow), and Panacea (Universal Remedy). Some sources also claim that he had three sons; Podalirius, Telesphoros, and Machaon.

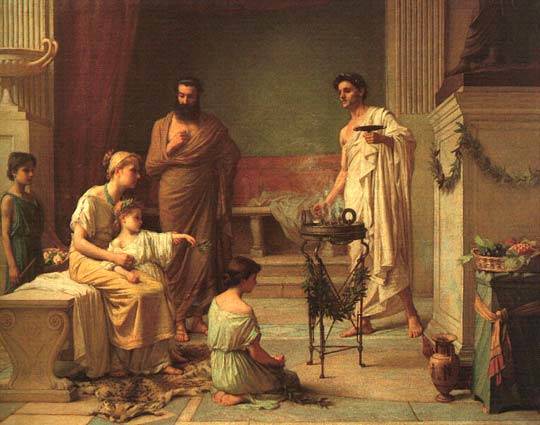

During the Classical Period, Asclepius’s main cult centre was Epidaurus, a settlement wedged in the north-eastern corner of the Peloponnese. As believers in heimarmene or fate would visit the Delphic Oracle to discover what lay in stall for them in years to come, so too did the ailing frequent ancient Epidaurus for the restoration of their health. Healing was sought in enkoimesis, the practice of sleeping in the innermost sanctuary of the Asclepian temple (the abaton) in hope that the god would unveil a remedy through dream states. Non-poisonous snakes, the earthly incarnations of the god, were sometimes allowed to slither amongst the sickly as they slept on the floor of the sanctuary. On the following day priests or priestesses would debrief the respective patients, offer an interpretation of the visions, and propose an appropriate course of action. Hence it would not be incorrect to say that the ministers of Asclepius were Hellenistic shamans–spirit-seers, dream-interpreters, and physicians all in one. They would frequently recommend, among other things, recurrent visits to baths and gymnasiums, as well as passive participation in comedies at Epidaurus’s colossal theatre. The Greeks believed that laughter was the best medicine for any illness, and the theatre at Epidaurus was used as a medium through which that inexpensive and natural mode of therapy could be trialled.

Asclepius’s sacred animal was the cock or rooster. His Latin equivalent is Aesculapius.