In classical mythology, Dionysus was the Greek god of wine and wine-making, merriment and drunkenness, as well as vegetation and fertility. His epithets “Acratophorus” and “Endendros”, two words meaning “giving unmixed wine” and “he of the tree”, connect the god to the aforementioned traits. The god was frequently depicted with an entourage of lesser deities including the Maenads, his female worshippers; the beautiful nymphs of Nyssa who raised him; and the lesser god Pan, a jovial and sexually-charged dwarf with the horns and hindquarters of a goat. Sometimes he was shown alongside the Sileni, shadowy forest men with the ears, tails, and legs of horses, and at other times he was attended by rustic pipe-playing fauns called Satyrs. As lower creatures of the earth, Dionysus’s male companions were all united by an orientation towards unrestrained pleasure-seeking or hedone. They were hostages of three principle carnal passions–drinking, singing, and having sex–that could not under any circumstances be transcended. Unrestrained, unmeasured, instinctual and reactive in their nature, these beings represent a substratum of being arrested by the laws of matter Dionysus differed from his polygamous companions in that he eventually married Ariadne, the fair daughter of Minos. According to Greek legend the god found the princess ashore the Aegean isle of Naxos where Theseus had forsaken her in his urgency to reach Athens. At first, his interest was purely fraternal but Ariadne’s disposition was of such a charming nature that he ultimately became enamoured of her. Together they had two children, Staphylus and Oenipon.

If one was to take Dionysius’s inexplicable connection to the cycles of birth, death and resurrection also exemplified by other gods like the Egyptian Osiris, the Semitic Tammuz, the Etruscan Atunis, and Phrygian Attis into consideration, then it would be feasible to suggest that he is either of Asiatic or Near Eastern origin. His primordial status as a pre-Hellenic deity is undisputed given that he was a god of the epiphany, a feature that originally belonged to the early matriarchal cults of the Great Mother Goddess. In Minoan Crete, one of the New Year rituals enacted by the priestesses of the Great Mother involved reaching a state of intoxication through the consumption of fermented mead followed by ecstatic dancing and culminating in the sacrifice of a bull intended to propitiate the earth. Similarly, the rites of Dionysus were built upon an intuitive ideology that unio mystica with the androgynous Unity that was the Godhead could be accomplished if one drank enough wine as to facilitate an altered state of consciousness.

Events of this type were called “orgia”, a word meaning “sacred works” in Greek. The ones most often connected to the cult of Dionysus were conducted biennially on the slopes of the beautiful Mount Parnassus and involved a multitude of female worshippers called Maenads or Bacchae that would scamper about in a histrionic state, scouring for natural agents of transcendence and transformation like wine or honey and tearing any unfortunate animal they happened to stumble upon to bits. Similar sacraments involving throated flutes and thundering drums were held in the Balkan Mountains or Haemus Mons, a region that many contemporary scholars believe formed the cradle of Dionysian worship. The reasoning behind this argument rests on the fact that many primary characteristics of Dionysian ritual worship like prayer, frenzied dancing, loud tribal music and animal sacrifice were assimilated by the Thracian cult of the Anastenaria, a religious yet institutionalised tradition associated with fire-walking that is still practiced in certain villages of Greece’s northern precincts on the Saint’s day of Constantine and Helena today.

Dionysus’s birth is definitely one of the stranger if not more bizarre incidences in the annals of classical mythology. He was the progeny of Semele, a daughter of King Cadmus of Thebes, and the mighty father of all Olympians, Zeus. As was often the case, the women who Zeus chose to bear his children usually became the unjust targets of Hera’s antagonism and jealousy and Semele was definitely no exception. One day, Hera appeared before Semele in the guise of an old crone and succeeded in poisoning her mind with doubts regarding the father of her unborn child. The wily Hera advised that the only solution to Semele’s problem was to request that Zeus appear before her in his true form, a spontaneous transformation that would validate his divinity. Knowing very well that mortals could not continue to subsist after seeing the true form of any god, Zeus beseeched Semele to retract her earnest petition but his cries fell on deaf ears. When the god materialised before her wreathed in bolts of thunder and flashes of lightening, Semele burst into flames and perished. Thankfully he managed to save the unborn child from her womb in time and sew it into a small corner of his thigh. The child was born on Mount Pramnos on the island of Icaria a few months later and raised initially by Semele’s sister Ino and later by the gorgeous oreads of Nyssa, a mountain in Asia Minor. When Dionysus reached manhood he travelled to Syria, Egypt, Phrygia and Greece proper to teach civilians the horticultural art of vinification (winemaking).

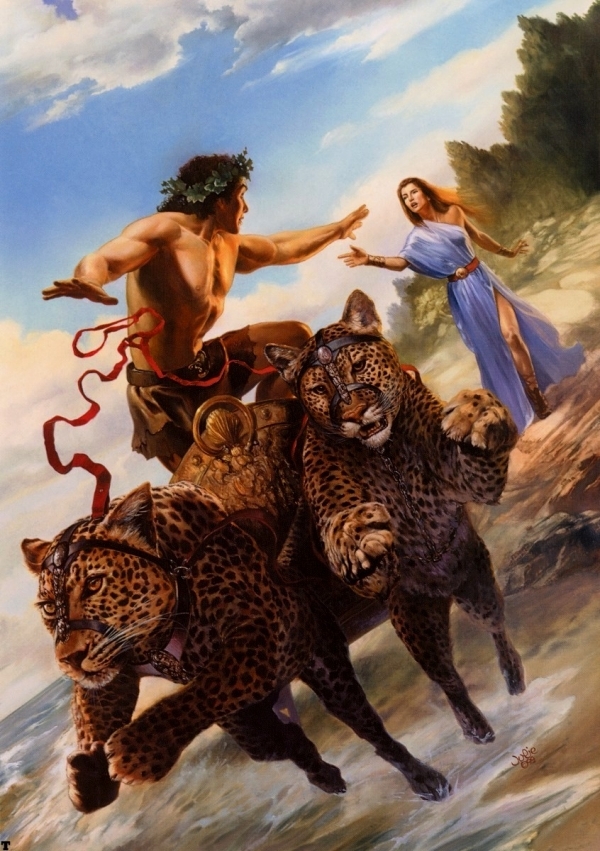

A pinecone-like tipped staff called a thyrsos and the ivy crown; plants like the grapevine and herbs like cinnamon, silver fir and birdweed; and animals like the leopard, the goat, the donkey, the lion, the serpent, and the wild bull were all sacred to Dionysus. His Roman equivalent is Bacchus.