Hera is the Olympian goddess of women and feminine sovereignty, as well as the sanctity of marriage. Her epithets Akraia (She of the Heights), Basileia (Queen) and Teleia (goddess of marriage) definitely attest to such. Together with Zeus, Poseidon, Hestia and Pluton (Hades), she comprised one of the many children of Cronus, or Father Time, and Rhea, the Earth Mother. Her intimate relationship with Zeus, sovereign of all gods and mortals, appears to have existed for time immemorial. Legend has it that Zeus caught glimpses of Hera as she scrambled up a mountain slope and decided on mere impulse that he had to have her. The goddess wouldn’t allow any god anywhere near her, so to trick her he morphed into a cuckoo and immediately instigated a torrential downpour. Seemingly apprehensive and sullen, the divine bird proceeded to fly through the rain and land, as if by chance, on Hera’s knee. Seeing the form of the trembling bird evoked the goddess’s empathy, who sought to remedy its anxiety by blanketing it with a corner of her dress. The sign of acceptance was Zeus’s cue to revert back to his usual form, and before long the two were enmeshed in an unruly embrace. For a long time Hera had nurtured countless reservations about making love with the free-spirited Zeus, but his pledge of allegiance and proposed marriage soothed her fears of abandon, at least enough to yield to his ravenous sexual appetite. Hera’s subsequent marriage to him yields additional titles and privileges, the most significant being her official recognition as the ‘Mother and Queen of Gods and Mortals’:

“Golden-throned Hera, among immortals the queen.

Chief among them in beauty, the glorious lady

All the blessed in high Olympus revere,

Honour ever as Zeus, the lord of the thunder.”

In all, the classical poets are barely, if ever, sympathetic to her plight. She is frequently made out as a malevolent, unevolved woman who acted out in bitter enmity and cruelty towards those she felt had wronged her. Furthermore, she had the memory of an African elephant; a past misdemeanour or insult was never under rug swept or forgotten. Her invectives became even more ruthless and calculating when it came to the human subjects and progeny of Zeus’s erotic escapades. Her hatred of her stepson Hercules, the spawn of Zeus and Alcmene, was profound and unrelenting. When he was still an infant, she conjured two serpents and sent them to his crib in hope that they might strangle him to death. Interestingly though, it was the snakes that drew the short straw. On another occasion she invokes the serpent Python to pursue a pregnant Leto unremorsefully to prevent her from giving birth to Artemis and Apollo, her divine twins to Zeus. Semele, the daughter of King Cadmus of Thebes, suffered Hera’s wrath for exactly the same reasons. Hera turned Lamia, a queen of Libya, into a gruesome monstrosity because she was loved by the king of gods. She even had the audacity to hurl her own self-generated infant son Hephaestus off the cliff because she believed wholeheartedly that she could not have given birth to such an ugly, handicapped creature.

In Homer’s Iliad, Hera heavily favours the Achaean (Greek) forces. The motivation behind her anti-Trojan sentiments is discernible if one peruses the wedding of King Peleus to the nymph Thetis, where the Trojan prince Paris eventually awarded the golden apple, a symbol of fairest beauty, to a goddess whose bribe was far more enticing than hers. For Hera having to submit to mortal judgement was a painstaking affair, but being demoted by a mere mortal was sacrilege, a violation of her self-worth. As a result, she did everything in her power to bring about the fall of Troy.

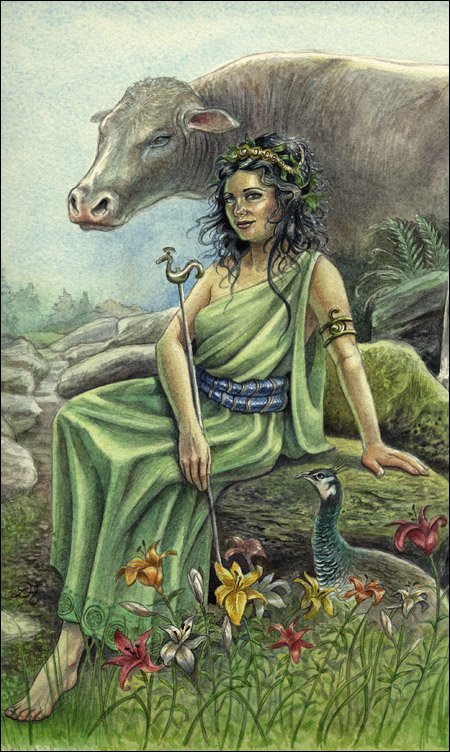

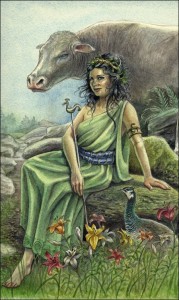

Sacred to the mother of gods and mortals was the cow, the pomegranate and the peacock. In the classical Hellenistic period she was often depicted being drawn across the heavens in a peacock-drawn chariot. Her Roman equivalent is Juno.