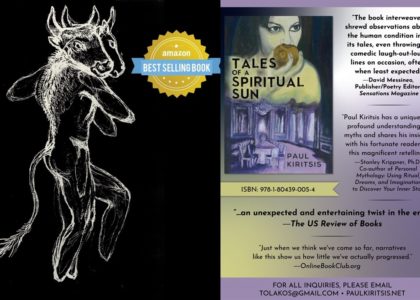

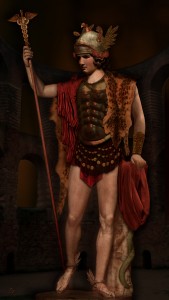

In classical myth the god Hermes acts the messenger of the Olympians, the living, tangible connection between the heavens and the earth, as well as a psychopomp. His epithets Diaktoros and Psychopompos definitely allude to the two just mentioned qualities. As Zeus’s chief emissary, his physical movements were fluid, swift and elegant, effortlessly transitioning between realms bedecked in beautiful ornaments most recognisable to the contemporary world: his feet were hugged by winged sandals; his head by a winged petasos or a wide-winged hat with a conical crown; and in one of his hands he always grasped the caduceus, a wing-topped magical golden staff or wand entwined with two snakes along its entire length. Hermes is a patron of travel, innovation and the arts, particularly of commerce and athletics, in addition to a shred master of trickery, appearances, facetiousness and oratory. As Hermes Eriounios, he also adjudicates over luck and serendipity.

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Hermes is the offspring of the invincible Zeus and Maia, the daughter of Atlas and the Oceanid Pleione. Like so many other universal deities, his mother gave birth to him in a secluded grotto. There are many classical sources that attest to the god’s wily nature, even as an infant:

“The babe was born at the break of day,

And here the night fell he had stolen away

Apollo’s herds.”

In reading these we learn that on a great many occasion Hermes would resort to mischief and imbroglio whilst his mother busied herself with daytime choirs. One time, he snuck out of his quarters and seceded in killing a tortoise before fashioning its shell into a lyre. After a while, playing the musical instrument had become mind-numbing so he attempted to muster personal satisfaction and delight by thieving cows from Apollo’s herd. Hermes’ plan of attack was meticulously planned and executed for the sake of evading detection; he diffused evidence that might be gained through reasoning by inverting body mechanics so that the path traced out by their tracks appeared inverse to what it actually was, and kept from making any footprints on the earth himself by binding severed branch stems onto the soles of his feet. After inciting some pandemonium at Pylos he aborted the self-serving endeavour and returned to his crib complacent and jubilant. But Apollo was not to be hoodwinked by the antics of his shrewd half-brother. After gathering sufficient clues including the anecdotal evidence of a witness to implicate him, Apollo appealed to the mighty Zeus on Olympus. After a short deliberation the latter succeeded in resolving their quarrel and hastening conciliation with a mutual exchange of gifts. Hermes handed over his maiden invention–the lyre–an instrument with which the musically-inclined Apollo was became intensely engrossed. In turn Apollo chose to part with his beloved shepherd’s crook, symbolically passing ownership of the herd over to his half-brother.

In Homer’s Iliad, the crafty Hermes takes the side of the Achaeans (Greeks). Aside from its evolution into a nine-year battle between the Greeks and the Trojans, the Trojan War was also the humus which facilitated the culmination of the gods’ own unresolved affairs. Hera, for instance, took on Artemis whilst Hermes was left to deal with Leto, the mother of Artemis and Apollo. Interestingly Hermes turns down the confrontation purely out of respect, a moral scrupulousness otherwise uncommon to his ascribed character. We encounter this unusual sentiment again as the plot thickens; in an act that might be seen as outright treachery for the banner he was supposed to be flying, Hermes leads King Priam of Troy to Achilles hut so that he may beseech the awesome demigod for the rightful return of his son Hector’s ravaged body.

Sacred to the messenger of the gods was the rooster and hawk, the ram and tortoise, as well as the crocus and strawberry plants. His Roman equivalent is Mercury.