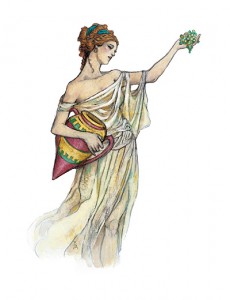

Hestia was the Olympia goddess of the hearth, domesticity and family, the latter being an entirely sacred denomination for the Greeks. Together with Artemis and Athena, she formed an exclusive association of virgin goddesses worshipped as the triune aspect of the Great Mother Goddess. According to some Hellenistic sources it is alleged that when the Titan Cronus, otherwise known as Father Time, tried to extirpate his own children for fear of being overthrown from the mount of heaven Hestia was swallowed first and regurgitated last. For this reason alone she stands at the helm of the Olympians as the oldest and youngest child of Cronus and Rhea, the Earth Mother. The others, as previously mentioned, are Demeter, Hera, Zeus, Poseidon and Hades. In scouring the annuls of classical mythology one can discern that she played a minimal role in its melodramatic, embellished episodes and its procession, though this is in no way an indicator of nominal influence in culture. In actual fact the goddess’s central importance to the bucolic conception of home and hearth is more often than not underrated and rudely dismissed. All sacrifices and meals made in a pastoral environment were heeded by an offering to the virgin goddess:

“Hestia, in all dwellings of men and immortals

Yours is the highest honor, the sweet wine offered

First and last at the feast, poured out to you duly.

Never without you can gods or mortals hold a banquet.”

She was of a serene, compliant and easy-going disposition, intensely aware of her immediate surrounds and vigilant in her relation with others. This is probably why she was seldom inveigled into partaking of trivial matters and exploits her fellow Olympians were notoriously known for. Poseidon and Apollo were both interested in courting her, though she politely repudiated their advances and pledged allegiance to the unsullied condition of virginity. Zeus, her beloved brother, honoured her oath and ensured she never succumbed to the carnal influences of wily Aphrodite or Eros. Sadly, Hestia’s incompetence in flowering into a full-blooded archetype influenced many classical thinkers in a way that often resulted in her exclusion from the Olympian pantheon of major deities, of which there was twelve. With respect to the latter, some philosophers gave preference to Dionysus, the god of wine, drunken merriment and sexual gratification. This uncertainty or vacillation between the two entities is immortalised in classical Athenian art and architecture. Hestia appears in the altar of the twelve Olympians at the Agora, but vacates her position for Dionysus on the eastern frieze of the Parthenon on the Acropolis.

The goddess of the hearth was inexplicably linked with everything homely, thus her sacred emblems were the kettle or pot, the cauldron, the crane bird, as well as the domesticated pug and donkey. Her Roman equivalent is Vesta.