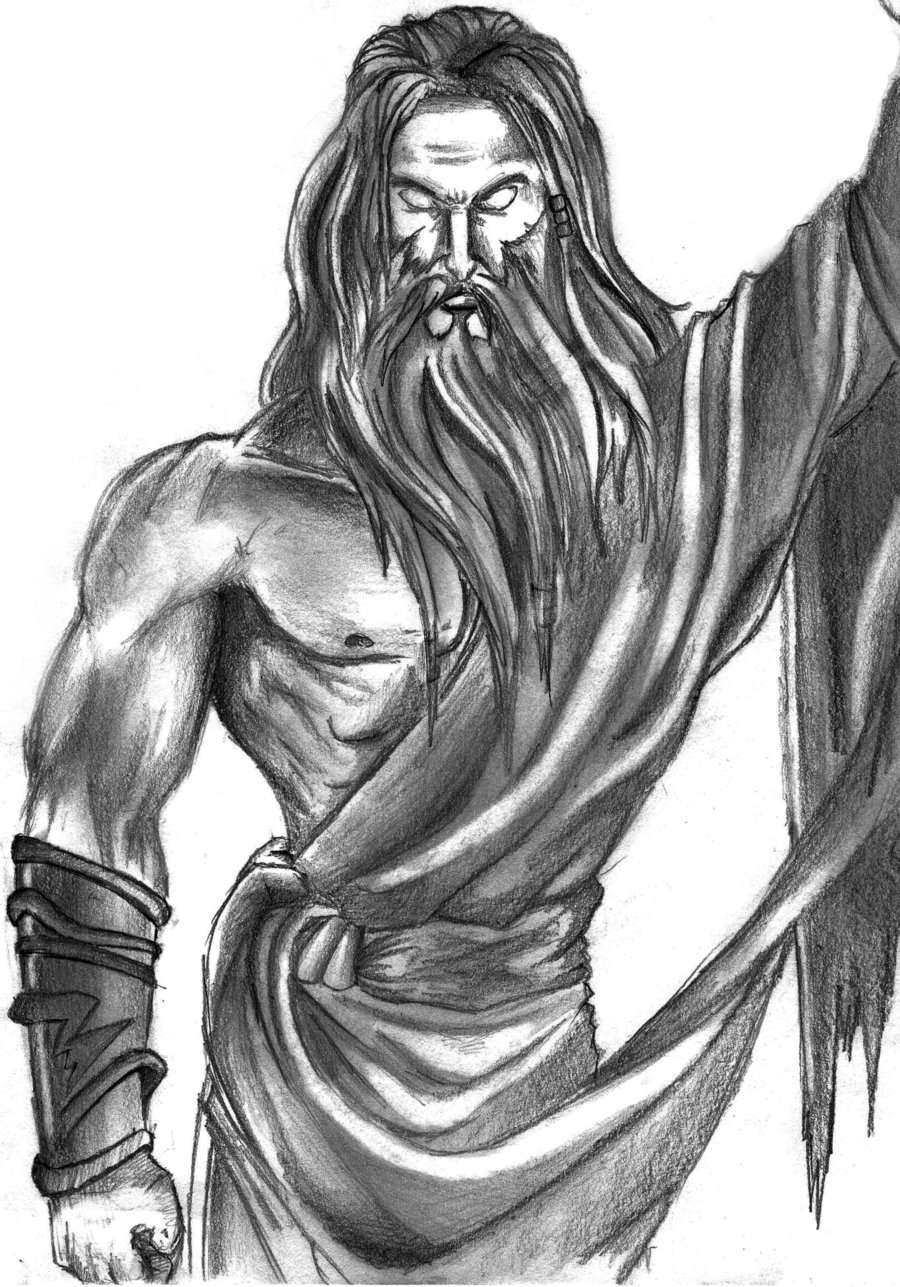

Zeus, the principle deity of heavenly Olympus and of classical Greece, appears to be a primordial entity that has been worshipped in the Balkan Peninsula from at least the third millennium bce. His name derives from dyeu, a Proto-Indo-European word which means “to shine” and connects the god to the sky, thunder and the heavenly realm in general. Zeus was the king of the stars and the rain, the conjurer of clouds and tempests. This symbolism was retained by classical consciousness which ascribed to the magnificent Zeus the epithets Tallaios, Astrapios, and Brontios to honour his celestial sovereignty. Hence when the commander-in-chief of the Hellenic forces, Agamemnon, invokes the god for help he chants, “Zeus, most glorious, most great, God of the storm-cloud, thou that dwellest in the heavens.”

In light of this it should come as no surprise that the eagle was foremost of his symbols and incarnations; the bird’s ability to ascend towards the cupola of the sky at mercurial speeds along with its propensity to hone in and dive upon its prey is both unprecedented and unrivalled by any other living creature. Hence the other zodiacal beasts (including human beings) that inhabited the earthly sphere were subject to his changing temperaments and mercy. Given that Zeus was responsible for weather and climactic change–themselves a symbol of portents and omens–the Greeks believed that he was a conspirator of fate or cosmic heimarmene, and that he could bend it to his personal will.

According to the classical sources, Zeus was the youngest child of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. In order to thwart an oracular prophecy which decreed that he would be overthrown by his own sire, Cronus proceeded to swallow six of his seven children whole–Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades and Poseidon. Zeus, on the other hand was saved from this lamentable fate, thanks to a conspiracy masterminded by his mother and grandmother, Rhea and Gaia respectively. He is then jostled to the shores of Crete to be raised by the nymph Adamanthea (or in some versions a goat named Amalthea) and the Kouretes, omnipresent soldiers who danced about smashing their shields with their swords as to mask the cries of the infant god. When Zeus came of age he squared off against his own father in combat and defeated him. During the violent altercation Zeus was able to inflict an abdominal wound that liberated his older siblings from the internal abyss. A violent battle known as the Titanomachy ensued between the two generations, in which Zeus and his siblings pugnaciously subdued the gruesome Titans and then hurled them into Tartatus, the shadowy depths of the Underworld. Atlas, the son of the Titans Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene, was to suffer the brunt of Zeus’ fury, inflicted with the burden of having to carry the weight of the heavens and the earth on his shoulders for all eternity.

When the hullabaloo subsided Zeus carved up the cosmos into three parts; to his brother Poseidon he gave the earthly waters, the ocean, and to Hades the realm of the deceased, the Underworld. The sky and the heavens he kept as his personal fiefdom. Even though he ordained only over a third of the cosmos, his supernatural powers and talents were many times superior to those of his fellow Olympians. He shrewdly reminds his divine brethren of this in Homer’s Iliad: “I am the mightiest of all. Make trial that you may know. Fasten a rope of gold to heaven and lay hold, every god and goddess. You could not drag down Zeus. But if I wished to drag you down, then I would. The rope I would bind to a pinnacle of Olympus and all would hang in air, yes, the very earth and the sea too.” With this awesome, sublime and insurmountable status came responsibility, and the classical texts frequently mention incidences where Zeus mediated over heavenly disputes in the manner that a judge or group of judges adjudicate over a criminal or civil trial. No matter whether one was a god, demi-god or mortal, recourse was to be found in consulting the mighty Zeus.

Like a great many men Zeus was an erotic, promiscuous, guileful and sexually-motivated individual. Polygamy was deeply ingrained in his being, in his genes even. There was no way he could ever be faithful to one person. His indecent liaisons with other goddesses, nymphs, women and men was a principal concern for Hera, his lawfully married sister, and much to her dismay a great deal of his time was spent trying to seduce or rape them. Without a doubt Zeus probably took as many partners and sired as many children as Ramses the Great (1303-1213bce). At one time Zeus attempted to befuddle his wife and divert her attention from his extramarital affairs by employing the nymph Echo to be her divine orator. Echo’s rampant banter worked for a little while, but when Hera grew sentient of her husband’s trickery she cursed Echo by decreeing that she should forever reiterate the words of others. Despite Zeus’s major flaw in character Hera tolerated and forgave her husband’s unremitting infidelity. Together they had five children: Ares, the god of war; Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth and midwifery; Hebe, the goddess of youth; Eris, the goddess of discord; and Hephaestus, the god of fire, metallurgy and the artisanal crafts. The latter is sometimes regarded as the offspring of Hera alone.

Zeus remains impartial in the Trojan War, favouring neither the Achaeans (Greeks) or Trojans. In fact his chief role during the course of the nine-year debacle is to enforce the law of heimarmene or fate, to bestow deserved honour upon the heroes irrespective of side and to ensure that none of the other Olympian deities involved can thwart or abort the predetermined outcome. Homer assigns him an unwavering, stoic, decisive and even merciless persona in the epic. For instance, in a mighty effort to appear impartial and moral Zeus deserts his own son Sarpedon to his own devices and pays a hefty price for it. During the battle Sarpedon squares off against a Patroclus decked in his lover’s armour (Achilles) and is mortally wounded, much to his father’s dismay. Zeus’s inertia in saving his own son was necessary, given that it demarcated the guidelines under which the Trojan War was to be played out; the gods or goddesses were not allowed to safeguard their vested interests or “pawns” if the action were to somehow thwart the trajectory of fate.

Zeus was the keeper of the aegis, a much-feared shield or buckler which could incite earthly pandemonium when rattled. Sometimes he would entrust this implement to Pallas Athena, his favourite child. Sacred to the god was the bull, the eagle and the oak tree. His Egyptian equivalent is Ammon-Re and his Roman counterpart Jupiter.